Learning objectives

- Learning

- Understand

- Integrate

- Reflect

|

Chronic subdural haematoma is a common treatable cause of dementia.

Introduction

- Subdural space between arachnoid and tough outer dura mater

- Subdural can be subtle and slowly growing over time

Aetiology

- Extra axial haematoma and not stroke so does not usually come under stroke team

- Bridging veins traverse the subdural space and are vulnerable to trauma especially when there is brain atrophy

- Occasionally can be due to the tear of a small cortical artery

Clinical aspects - can be incredibly subtle

- Headache, weakness, altered vision, altered speech, focal seizures

- Stroke like but more subtle with no definite onset time in an older patient

- TIA like episodes related to irritation of underlying cortex

- Coma and low GCS due to raised ICP

- Seen in the setting of trauma which may be mild to severe

- Consider if patient on anticoagulants

- Worsening confusion or dementia

- Unsteadiness and difficulty walking

- Apathy, lethargy, or drowsiness

- Behaviour and personality changes, memory loss

Risks

- Old age - this is the leading risk factor for having SDH's

- Taking antiplatelets or anticoagulation therapy

- Blood clotting disorder

- Alcohol abuse

- Frequent falls

- History of repeated head injuries

- Having an intracranial shunt

Classification

| Type | Notes | Imaging | Management |

|---|

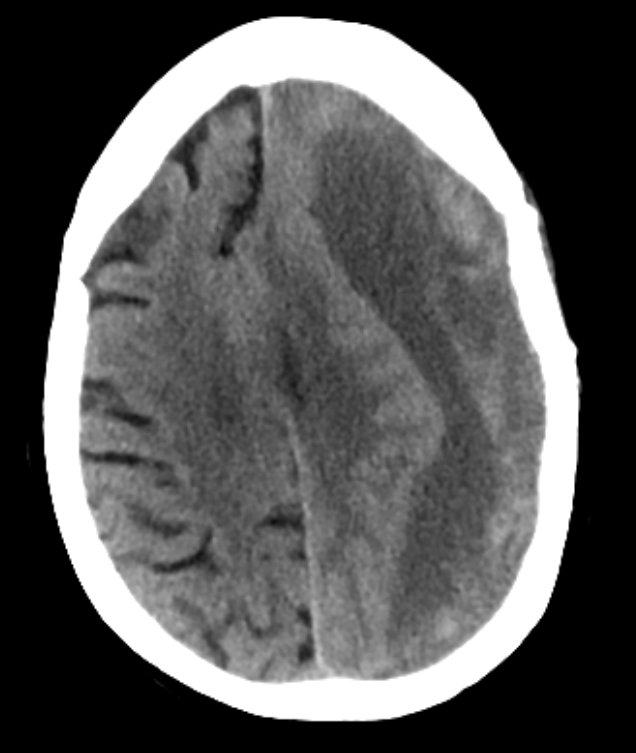

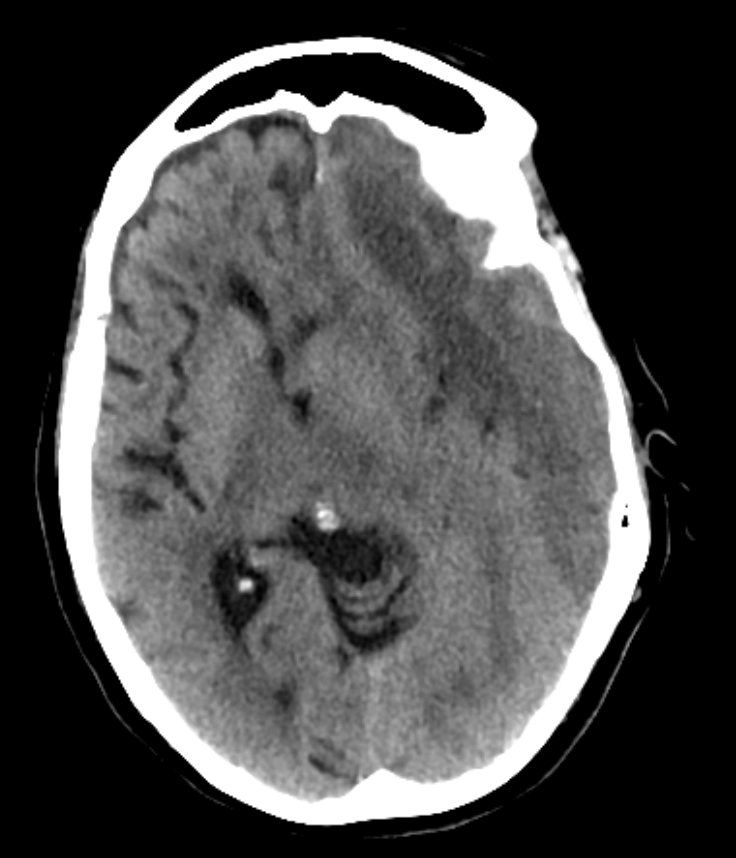

| Acute | usually within 24-72 hours of trauma. | Bright white fresh blood and possibly a fluid level | Stop anticoagulation and urgent neurosurgical consult and possibly emergency surgery. This usually is a craniotomy where a larger section of the skull is removed, the clot is lifted out, and the skull plate replaced.

|

| Subacute | Presents after 72 hours. | Darker blood with some mottled blood products and possibly a fluid level | Stop anticoagulation and urgent neurosurgical consult and semi-elective surgery if required |

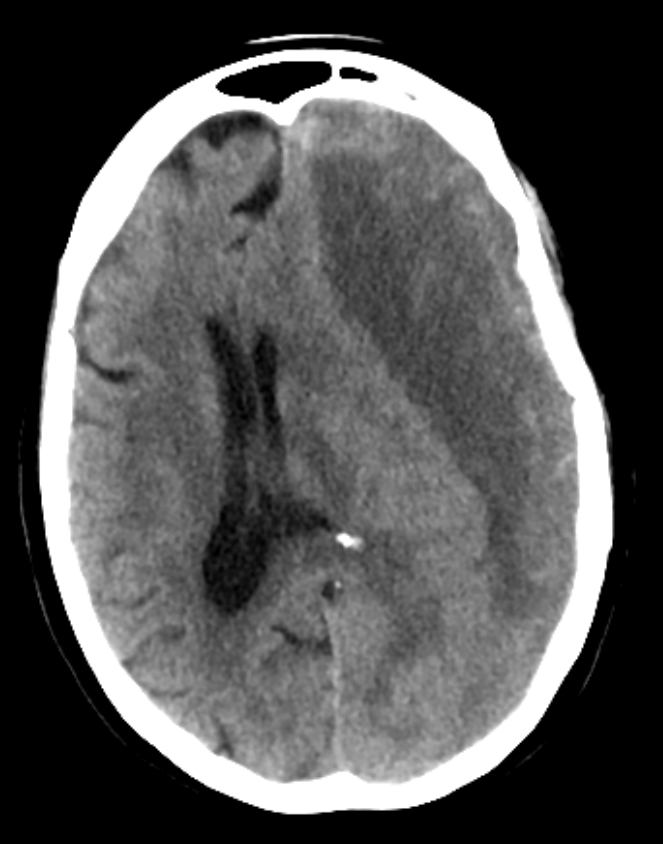

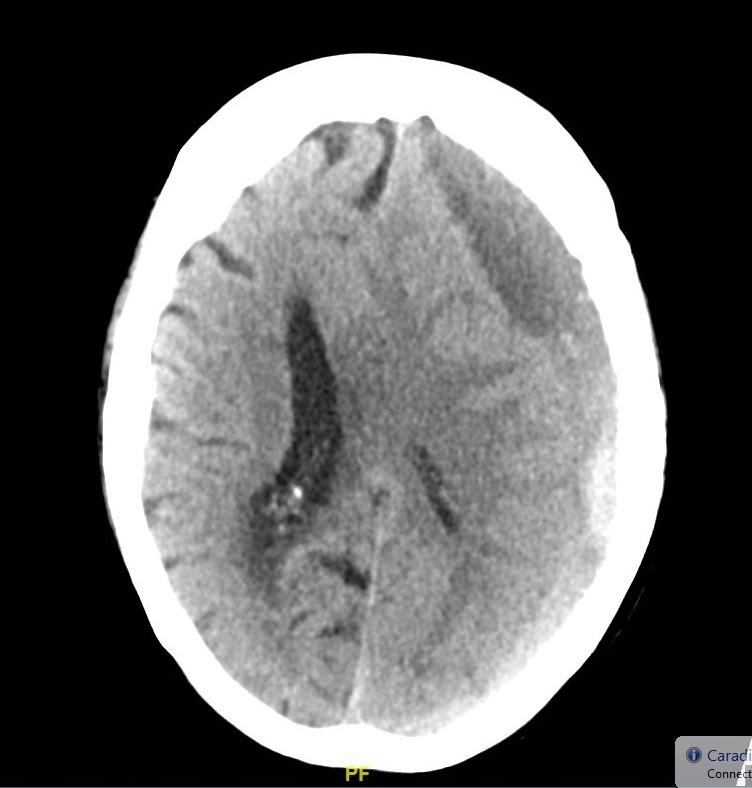

| Chronic | May take weeks or even months to appear | Usually uniformly dark with asymmetry of subdural spaces and possible shift | Stop anticoagulation and neurosurgical consult and elective surgery usually using Burr hole trephination where surgeons drill a hole through the skull above the clot and wash it out with copious irrigation. This is only possible with liquefied haematomas so for Chronic SDH. Some may not need any surgery and resolve with time |

Investigations

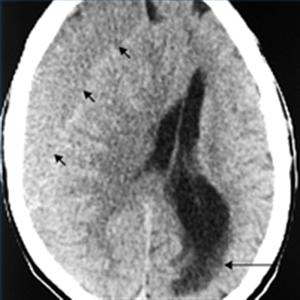

- CT scan is diagnostic usually and not subtle. However, a very small SDH can be easily missed. usually asymmetry of the subdural space on CT may be the clue. Blood may be acute "bright white" or less acute and mottled as it becomes subacute. Over time it becomes darker. There may be a fluid level in the subdural space. At some points a SH can become isodense to brain and can even be missed. MRI is indicated if not sure.

- MRI is helpful when there are subtle changes. The blood sequences will show a rim of subdural blood.

Differentials

Management

- Small subdural haematomas with mild symptoms may require no treatment beyond observation. Repeated head scans will likely be needed to monitor haematoma size and trends and stopping anticoagulation in the short term.

- In the comatose patient due to an acute SDH with fresh bleeding then definitive management is to reverse anticoagulation and stop antithrombotic and emergency Neurosurgery which will usually involve a craniotomy/craniectomy to remove the haematoma and ITU care.

- In the stable patient the Neurosurgeons may delay surgery until the clot has liquefied and can be taken out via burr holes. Again anticoagulation should be stopped. In this situation with stable patients they may be managed as outpatients as long as they are closely supervised for any worsening.

- Long term management of antithrombotic and anticoagulants needs to be decided on an individualised basis.

References