The role of neurosurgery has become more clearly defined by an accumulation of evidence over the years such that surgery for supratentorial bleeds is becoming increasingly uncommon. A more defined use for surgery is in decompressive procedures for ischaemic strokes. The neurosurgical management of Aneurysmal SAH and subdural haemorrhage (technically not stroke as extra-axial) are a significant proportion of neurosurgical workload and each is discussed under their specific articles.

Neurosurgery is underpinned by the rigid "bony" box principle. The skull is a box within which lies the soft structure of the brain. Anything that causes trauma to the box or its contents will cause an increase in volume of the brain which if left unchecked can lead to progressive damage, dysfunction and ultimately death. Neurosurgery attempts to find ways to relieve the increased intracranial pressure before permanent damage can be done, or to limit any permanent damage to the minimum. These principles underpin neurosurgical management of stroke and its complications. Make that sure you have read the basic chapter on the Munro-Kellie hypothesis.

Malignant MCA syndromes and Decompressive Hemicraniectomy

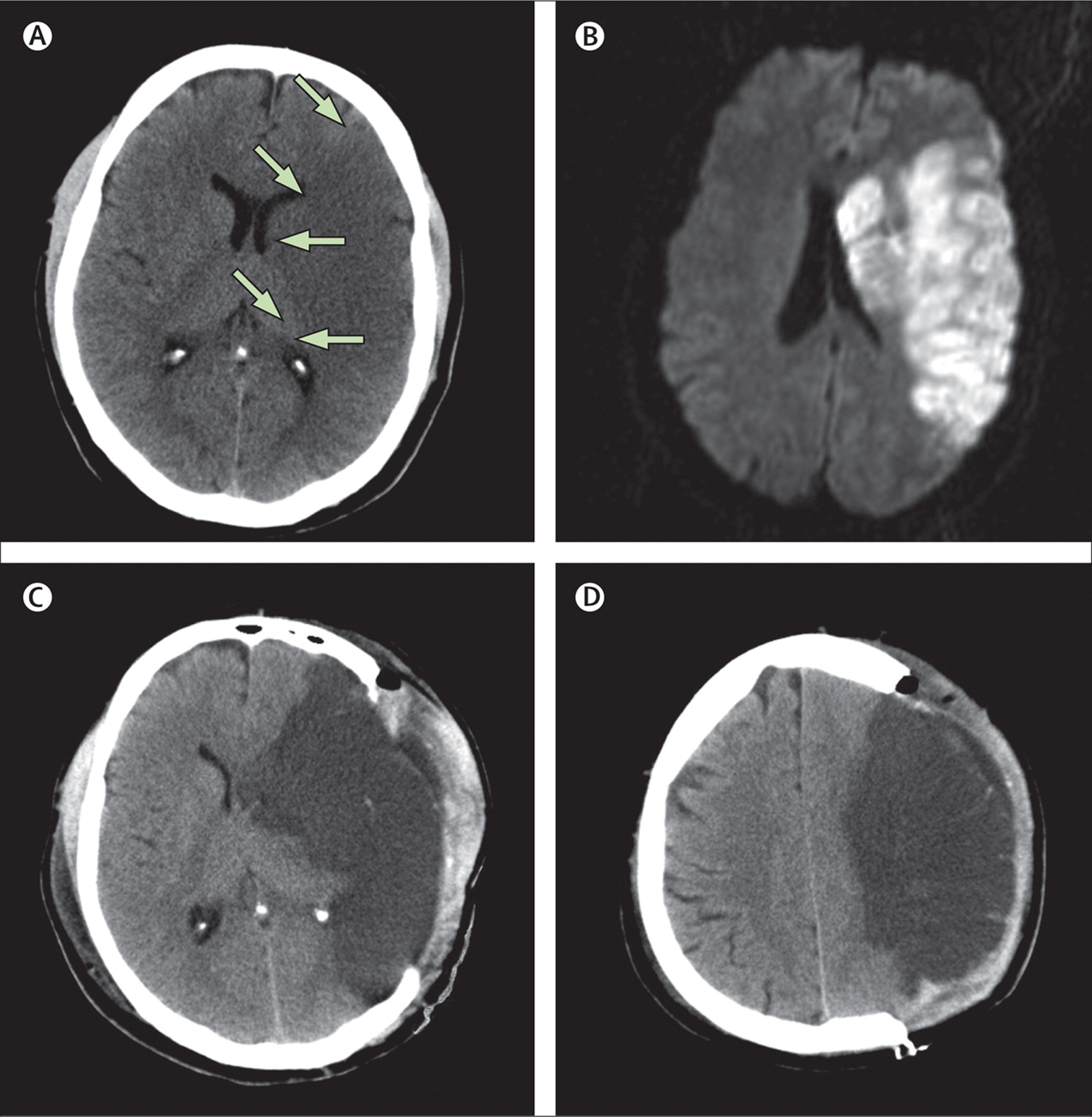

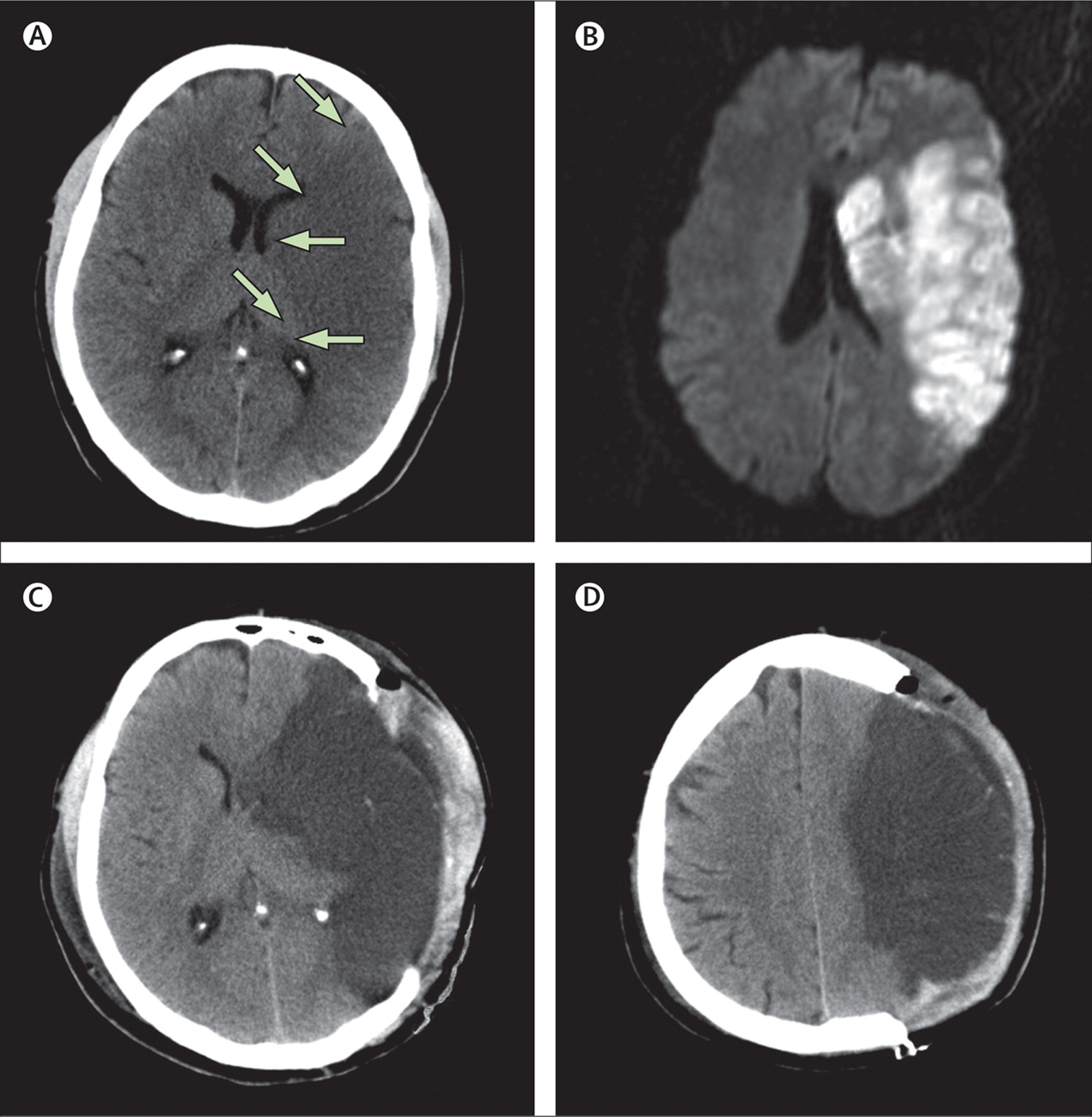

Decompressive hemicraniectomy with durotomy is a procedure first pioneered by Harvey Cushing the famous Boston neurosurgeon in 1905 [Cushing H 1905]. It did not come into usage for stroke until 1956. It has had several uses over the years but it is more so being used now for those with complete occlusion of the distal internal carotid artery or proximal (M1) of the middle cerebral artery. Malignant MCA infarction is seen in about 10% of infarcts and the patient presents with a severe hemiparesis, gaze palsy with eyes deviated away from the side with the weakness and hemisensory loss. Consciousness may be impaired possibly due to raising Intracranial pressure. There will be severe aphasia or neglect depending on the side affected. There is a concern that operating on those with dominant hemisphere malignant MCA syndromes may lead to poor outcome with aphasia and hemiparetic patients. However, this has been challenged and each case must be judged individually.

There is progressive oedema due to a break down in the blood brain barrier and this tends to peak at approximately 48 hours post stroke. This can lead to trans tentorial herniation and death. Needless to say the prognosis is poor and disability in survivors likely to be severe. A small number of studies have shown that removal of the skull on the affected side and allowing herniation of the brain can reduce ICP and can reduce mortality by about 35-50%. Early intervention within the first 24 hours appears to be better. Therefore, in a DGH setting these patients need screened and identified early and plans made to move possibly to their stroke unit for joint stroke physician and neurosurgical consultation.

The procedure involves bone removal which reduces the ICP by about 15% but then in addition to this the dura is incised and this reduces ICP by 70%. Strokectomy that is the incision and removal of infarcted brain is generally not advocated with the concern that penumbra may be being removed. A large skin flap is fashioned. Bone is removed. The skull flap can be retained and used later in the plastic reconstruction of the wound some weeks or months later [Samandouras G.2011] Until that is done there is an obvious skull defect and the brain covered only by soft tissue remains vulnerable to injury.

A post mortem study showed that this was more common in the young, females, those with no prior history of stroke, an abnormal ipsilateral circle of Willis, an increased heart weight and those with carotid occlusion. [Jaramillo et al. 2006]. Various other imaging techniques including DWI, Perfusion studies have all been used to try and identify patients at risk. Serum markers are under study and these include Plasma cellular fibronectin and Serum S100B which are signs of cellular injury. In practice however CT or MRI if available acutely are the main investigations.

| Current Selection Criteria: These vary from centre to centre and local guidance will be needed. RCP guidance suggest the following should be considered |

|---|

- Aged 60 years or younger

- Clinical deficits suggestive of infarction in the territory of the middle cerebral artery

- NIHSS of above 15.

- Decrease in the level of consciousness to give a score of 1 or more on item 1a of the NIHSS

- Signs on CT of an infarct of at least 50% of the middle cerebral artery territory, with or without additional infarction in the territory of the anterior or posterior cerebral artery on the same side, or infarct volume greater than 145 cm3 as shown on diffusion-weighted MR

|

Malignant MCA territory infarction is not a contraindication to intravenous thrombolysis. Intravenous thrombolysis is not a contraindication to hemicraniectomy.

Evidence base

The evidence base for hemicraniectomy is based on several small studies. The DECIMAL trial [ Vahedi K et al. 2007] was randomised and looked at surgery in patients aged 18 to 55 and their subsequent modified Rankin score. The trial was stopped after 38 patients were enrolled as there was a 52.8% reduction in death in the treated group. The DESTINY trial [Juttler E et al. 2007] was randomised and controlled and was again able to show a significant reduction in mortality post surgery despite only 32 patients being included. The HAMLET [Hofmeijer J 2009] study again looked at surgery and included 64 patients and showed benefits in mortality up to 48 hours but not beyond. These were the three European surgery trials and on their data was pooled [Vahedi K et al. 2007].

The Cochrane database states :- Surgical decompression lowers the risk of death and death or severe disability defined as mRS>4 in selected patients < 60 years of age or younger with a massive hemispheric infarction and oedema. Optimum criteria for patient selection and for timing of decompressive surgery are yet to be defined. Since survival may be at the expense of substantial disability, surgery should be the treatment of choice only when it can be assumed, based on their preferences, that it is in the best interest of patients. Since all the trials were stopped early, an overestimation of the effect size cannot be excluded. [Cruz-Flores S et al. 2012]

The results imply that surgical intervention decreased mortality of patients with fatal middle cerebral artery infarct at the expense of increasing the proportion suffering from substantial disability at the conclusion of follow up. Patient selection is key. My own experience is that the very small number of young patients who I have referred and had surgery that outcome was surprisingly good and patients have returned to almost complete functional independence. Hemicraniectomy is clearly aggressive therapy and may not be appropriate for many patients and their families.

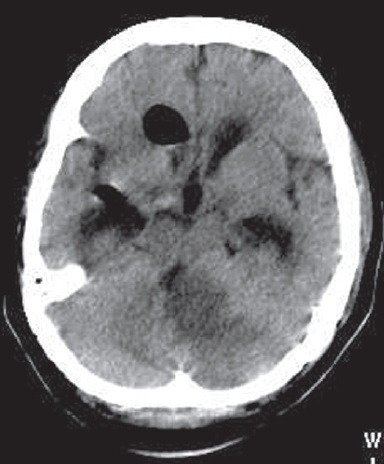

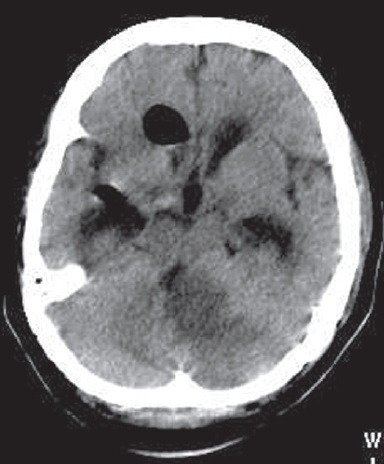

Posterior Fossa Infarcts and malignant Cerebellar Infarction

The posterior fossa is an even smaller tighter space and Cerebellar infarcts can cause swelling and increased pressure within the posterior fossa leading to compression of the IVth ventricle and hydrocephalus - so call "cerebellar apoplexy" or malignant Cerebellar Infarction. Imaging may show loss of the basal cisterns and brainstem compression. Deteriorating patients with a falling GCS can benefit from surgical management [Mohsenipour I et al. 1999]. Suboccipital Decompressive Craniectomy has risk but is well tolerated in patients with malignant cerebellar infarction. The oedema often peaks at around 2-3 days. Infarct- but not procedure-related early mortality is substantial. Long-term outcome in survivors is acceptable, particularly in the absence of brain stem infarction. Developing symptomatic hydrocephalus should be considered for external ventricular drainage (EVD) or less commonly by ventriculo-peritoneal shunting. Upward herniation is always a risk. A failure of EVD in managing hydrocephalus or ongoing brainstem compression can necessitate suboccipital decompressive craniectomy. Discuss with neurosurgeons early particularly in younger patients with a good baseline.

References

- Vahedi K, Vicaut E, Mateo J, et al. Sequential-design, multicenter, randomized, controlled trial of early decompressive craniectomy in malignant middle cerebral artery infarction (DECIMAL Trial). Stroke 2007; 38:2506. link

- DESTINY II Study Group DESTINY II: Decompressive Surgery for the Treatment of malignant Infarction of the middle cerebral artery II. International Journal of Stroke & 2011 World Stroke Organization Vol 6, February 2011, 79-86

- Juttler E, Schwab S, Schmiedek P, et al. Decompressive Surgery for the Treatment of Malignant Infarction of the Middle Cerebral Artery (DESTINY): a randomized, controlled trial. Stroke 2007; 38:2518.

- Hofmeijer J, Kappelle LJ, Algra A, et al. Surgical decompression for space-occupying cerebral infarction (the Hemicraniectomy After Middle Cerebral Artery infarction with Life-threatening Edema Trial [HAMLET]): a multicentre, open, randomised trial. Lancet Neurol 2009; 8:326

- Pfefferkorn T et al. Long-Term Outcome After Suboccipital Decompressive Craniectomy for Malignant Cerebellar Infarction Stroke. 2009;40:3045-3050 Link