Learning objectives

- Learning

- Understand

- Integrate

- Reflect

|

Introduction

- Cerebral amyloid angiopathy (CAA) is a common cause of ICH in the elderly

- There is deposition of beta amyloid in the walls of small and medium-sized blood vessels [Pantoni 2010].

- CAA is a distinct cerebral process alone and is unrelated and should not be confused with the systemic amyloid deposition diseases.

- A more inflammatory variant of CAA which can be steroid responsive has been detected [Moussaddy 2015].

Aetiology

- Deposition of amyloid-ß fibrils in the wall of the small and medium-sized blood vessels, mostly arteries of the leptomeninges and cerebral cortex.

- CAA has been found commonly in those with Alzheimer disease.

- Only a minority of those with CAA develop Alzheimer disease.

- There is an increased risk of dementia in those with ICH.

Genetics

- There is a genetic association with apolipoprotein E gene epsilon 2 and 4 alleles.

- Hereditary forms of CAA are generally familial (rare), more severe and earlier in onset. These are

- Dutch type: late middle age. ICH. Amyloid deposition. Some get dementia. Defect in amyloid protein precursor protein (APP) gene on chromosome 21.

- Icelandic type: Presents young adults with ICH. Dementia seen. Involves brainstem and cerebellum too. Mutation of the cysteine protease inhibitor cystatin C.

Pathology

- Cerebral amyloid angiopathy is a major cause of haemorrhagic stroke in older patients. There is localised amyloid deposition which increases vessel wall fragility which leads to increased bleeding risk.

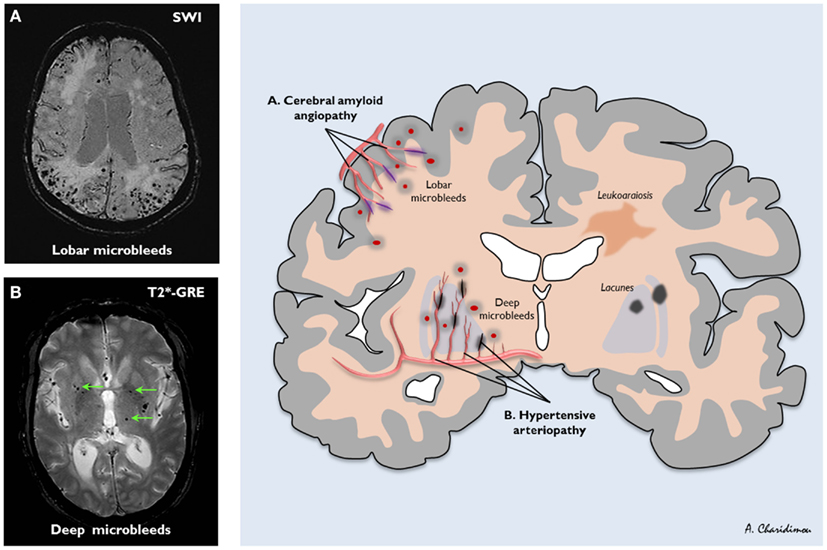

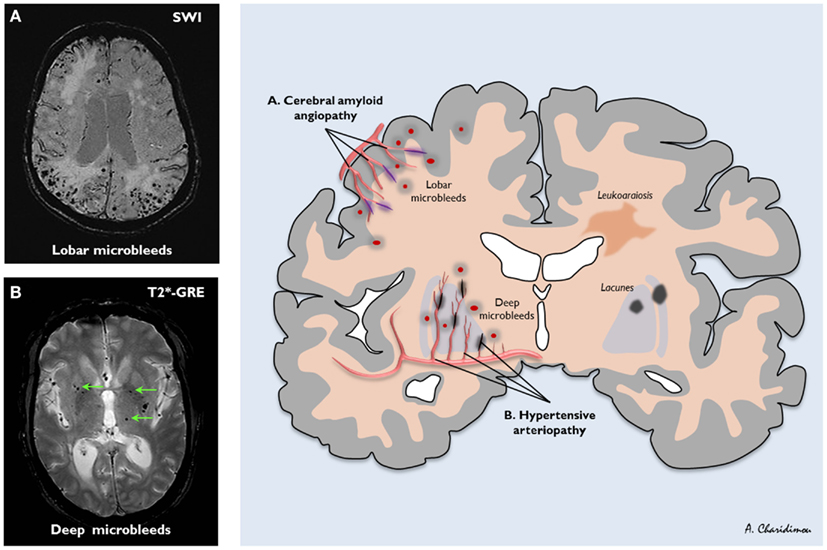

- Suspect amyloid if lobar bleeds are seen in those over age > 70 without evidence of pre-existing hypertension. By lobar we are referring to the cortex and subcortical white matter in distinction to the deep hypertensive bleeds affecting putamen, thalamus and pons.

- CAA bleeds are slightly commoner in temporal and occipital lobes rather than frontal and parietal lobes. The main differentials of a lobar bleed will be extension from a large putaminal haemorrhage, Haemorrhagic transformation of an infarct, arteriovenous malformation (AVM) or Haemorrhagic tumour.

- Histological examination reveals the deposition of β-amyloid in the media and adventitia of small and mid-sized arteries (and, less frequently, veins) of the cerebral cortex and the leptomeningeal amyloid

Cerebral Amyloid Angiopathy Related Inflammation (CAA RI)

An inflammatory form of amyloid often with distinct MRI changes which may not always parallel clinical changes has been found and is called Cerebral amyloid angiopathy-related inflammation. Has also been called cerebral amyloid angiitis and cerebral amyloid inflammatory vasculopathy. CAA-RI as it is termed presents with focal neurology and imaging demonstrates vasogenic oedema involving the subcortical white matter with possible some leptomeningeal enhancement and microbleeds are seen.

Clinical

- Clinically the course can be recurrent as there is a predisposition to further bleeds. Bleeds may be brought on by falls or trivial trauma. Some cases can be relentless with reoccurring bleeds which follow an initial event, a sort of 'primary progressive' pattern. These are then followed over a year or so by further anatomically related and unrelated lobar bleeds for which little can be done other than to stop all anticoagulants and look at falls risk and manage any co-existing blood pressure which may coexist.

- As soon as the patient gets over one episode they come back with a further. Patients with CAA can simply have transient neurology with a TIA like syndrome or focal seizure type episode. A real concern when many of us do TIA clinics with limited access to MRI and an assumption that such episodes are most likely thrombotic. CT is unlikely to pick up small especially non acute microbleeds especially as presentation to the TIA clinic may be after days or even weeks.

Diagnosis

| Boston Criteria for Amyloid Angiopathy |

|---|

| Definite cerebral amyloid angiopathy | a full post-mortem examination reveals lobar, cortical, or cortical / sub-cortical haemorrhage and pathological evidence of severe cerebral amyloid angiopathy. |

| Probable cerebral amyloid angiopathy | with supporting pathological evidence :

clinical data and pathological tissue (evacuated haematoma or cortical biopsy specimen) demonstrate a haemorrhage as mentioned above and some degree of vascular amyloid deposition. Doesn't have to be post-mortem |

| Probable cerebral amyloid angiopathy | Pathological confirmation not required. Patient older than 55 years. Appropriate clinical history. MRI findings demonstrate multiple haemorrhages of varying sizes / ages with no other explanation. |

| Possible cerebral amyloid angiopathy | Patient older than 55 years with appropriate clinical history. MRI findings reveal a single lobar, cortical, or cortical / sub-cortical haemorrhage without another cause, multiple haemorrhages with a possible but not a definite cause, or some haemorrhage in an atypical location. |

The Boston criteria were first proposed to standardise the diagnosis of cerebral amyloid angiopathy. They comprise of combined clinical, imaging, and pathological parameters. They provide a useful list of criteria for research and comparing similar groups of patients. Using these criteria in most cases without post-mortem or brain biopsy we can therefore only suggest that our patients have Probable or Possible CAA.

Imaging

- CT Brain: acutely this will show a single or possibly more than one lobar haemorrhage in a superficial location. There maybe local extension to the subarachnoid or into the ventricles. As time passes there may be an accumulation of bleeds. Bleeds tend to be more common in the frontal and parietal lobes both cortically and subcortical. Posterior structures including cerebellum and deep nuclei can be affected but usually the traditional sites for hypertensive bleeds such as putamen, thalamus and pontine are avoided.

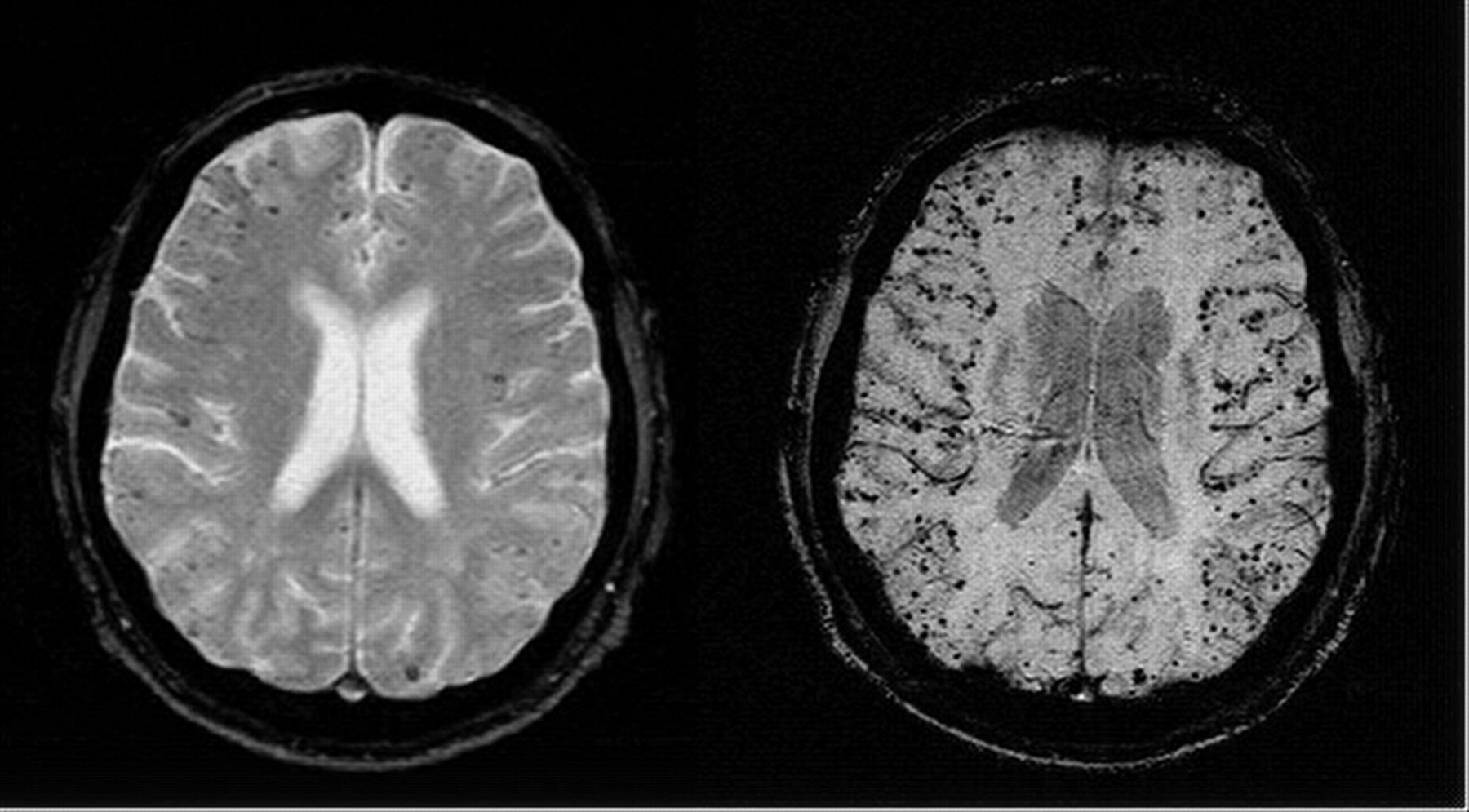

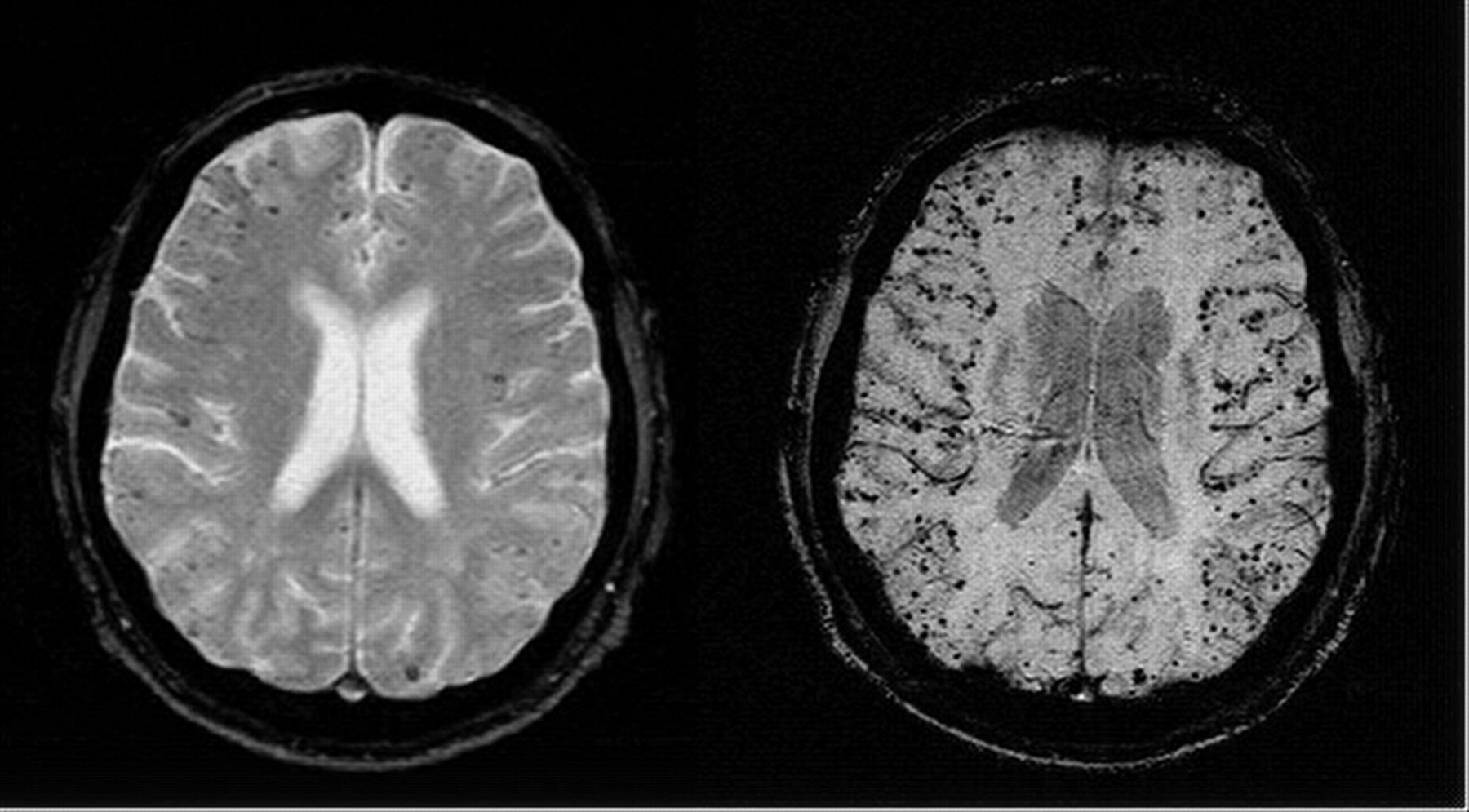

- MRI Brain: using the Gradient echo or T2* sequences is very sensitive at detecting haemosiderin a break down product of blood and therefore indicating evidence of old bleeds.

- Brain Microbleeds may suggest subclinical CAA. They are seen in 5-20% of the population depending on population studied and radiological techniques in their imaging diagnosis [Rosand J et al. 2000]. These have been defined radiologically as homogeneous, round foci, < 10 mm diameter (no minimum size was specified), of low signal intensity on GRE T2*-weighted MRI.

- They need to be differentiated from lesions compatible with an infarct with haemorrhagic transformation [Cordonnier et al. 2009].

- Microbleeds are commoner in those taking anti-thrombotic agents. Those with CAA RI will usually have dramatic T2 changes of oedema which may be out of proportion to clinical signs.

- CTA/MRA/CTV: may be needed when other aetiologies are being considered.

- PET brain imaging: is very much a research tool

- Genetic studies where needed in those with suspected familial disease may show apoE e4/e4 genotype

- Biopsies taken at surgery or post mortem the brain will show amyloid with congo red staining

Cerebral Microbleeds (CMBs)

Enigmatic radiological changes seen on certain imaging modalities. Importantly not seen on CT or standard MR. They are defined radiologically as small, rounded, homogeneous, hypointense lesions on T2*-weighed gradient-recalled echo (T2*-GRE) and related MRI sequences that are sensitive to magnetic susceptibility. Histopathological correlation suggests that they are due to tiny bleeds adjacent to abnormal small vessels, usually due to chronic hypertension or cerebral amyloid angiopathy (CAA). There is an association with cerebral haemorrhage, cognitive decline and Alzheimers but also seen in older population. Exact risks are being determined as it adds another issue to the concerns and difficulty of decision making around using antithrombotic and anticoagulation in many patients at risk of thromboembolic disease.

Inflammatory CAA now called Cerebral amyloid angiopathy-related inflammation (CAA-ri)

Can closely mimic primary angiitis of the central nervous system. It is a relatively rare syndrome. Diagnosis usually made on biopsy. Responds to steroids. There may be lobar, white matter, nonenhancing hyperintensities on T2-weighted sequences.Positron emission tomographic scan may show diffuse uptake of 11C-Pittsburgh Compound B in inflammatory cerebral amyloid angiopathy [Moussaddy 2015]. There are two subtypes which are inflammatory CAA (ICAA) and amyloid-ß-related angiitis (ABRA) according to histopathology. ABRA is preferred if the lesion enhances on MRI and requires combination drug therapy. ICAA is highly suspected with ApoE genotype of ?4/?4 [Chu et al. 2016].

Possible Complications

- Repeated episodes of bleeding in the brain

- Hydrocephalus, Seizures , Dementia, Death from ICH

Management

- Avoid antiplatelets and antithrombotics and thrombolysis. Standard care for Haemorrhagic stroke including surgery

- Falls prevention strategies can be useful where appropriate

- Good management of hypertension and vascular risks

- Long term dementia and seizure care may be needed

- CAA RI: A significant proportion of patients respond readily to treatment with treatment with corticosteroids. Take expert help.

References

- Pantoni L. Cerebral small vessel disease: from pathogenesis and clinical characteristics to therapeutic challenges. LancetNeurol 2010;9:689-701.doi:10.1016/S1474-4422(10)70104-6

- Moussaddy, et al. Inflammatory Cerebral Amyloid Angiopathy, Amyloid-ß-Related Angiitis, and Primary Angiitis of the Central Nervous System Similarities and Differences. Stroke. 2015;46:e210-e213.

- Chu et al. Cerebral Amyloid Angiopathy (CAA)-Related Inflammation: Comparison of Inflammatory CAA and Amyloid-ß-Related Angiitis. Journal of Alzheimer's Disease, vol. 51, no. 2, pp. 525-532, 2016.

- Andreas Charidimou, Clare Shakeshaft and David J. Werring. Cerebral microbleeds on magnetic resonance imaging and anticoagulant-associated intracerebral hemorrhage risk. Front. Neurol., 19 September 2012

- Knudsen KA, Rosand J, Karluk D et-al. Clinical diagnosis of cerebral amyloid angiopathy: validation of the Boston criteria. Neurology. 2001;56 (4): 537-9.

- Cerebral Amyloid Angiopathy: A Systematic Review. J Clin Neurol 2011;7:1-9

- Amyloid imaging at radiopedia