Learning objectives

- Learning

- Understand

- Integrate

- Reflect

|

Introduction

Cerebral Venous (Sinus) Thrombosis (CVST) refers to thrombosis and occlusion of venous or venous sinus channels in the cranial cavity. It is rare causing less than 1% of strokes. Classically the patients are young, female and procoagulant - pregnancy, puerperium, inherited thrombophilia, on OCP but all ages and both sexes are at risk. The presentation can be subtle. You need to consider it to get a CTV or MRV to diagnose it. CVST can cause cerebral haemorrhage as well as infarction. Where there is a venous prothrombotic state and new central neurology one should always ask - could this be venous thrombosis. Always consider in those with new persisting central neurology and/or headache in pregnancy or the puerperium. If it enters the diagnostic differential, then imaging should be seriously considered, and anticoagulation started once diagnosis confirmed. Greater access to MRV has resulted in increasing diagnosis of cerebral venous disease and recognition that it is commoner and there may be milder forms.

Classification

- Dural venous thrombosis: affecting Superior sagittal sinus, Lateral sinuses, Straight sinus, Cavernous sinus

- Cortical vein thrombosis: affecting smaller veins on cortical surface

- Deep cerebral vein thrombosis: prognosis often poor due to bilateral thalamic infarction affecting diencephalon

Pathophysiology

- All organs require venous drainage and that includes the brain. Flow is high to match the high brain perfusion.

- Venous outflow from the brain is into a collection of different channels or sinuses and then into the internal jugular vein.

- Diseases and thrombosis of the veins are rare compared to the arterial supply.

- Cerebral venous thrombosis usually progresses to venous infarction

- Increasing access to improved imaging has led to increased diagnosis of this condition.

- There are superficial veins which lie in the subarachnoid space and drain the cerebral cortex and empty into the venous sinuses.

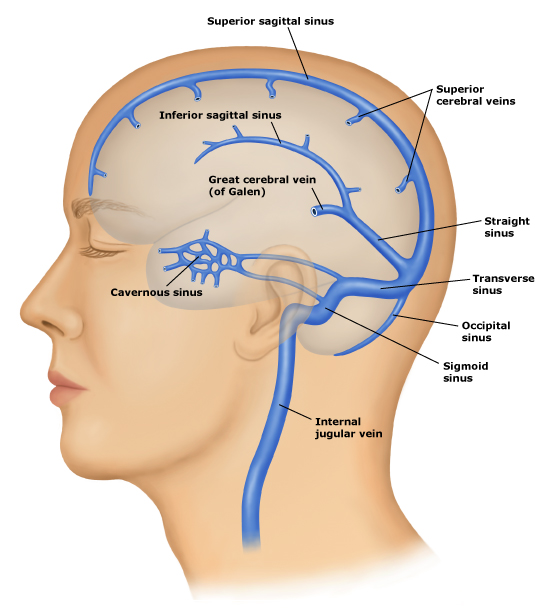

Anatomy

- Cerebral veins and sinuses lack valves and tunica muscularis. Absence of valves permits blood flow in various directions while absence of tunica muscularis permits veins to remain dilated.

- Venous sinuses are located between two rigid layers of dura mater. This prevents their compression when intracranial pressure rises.

- Communication between various venous sinuses either via communicating veins or through merger into each other especially at torcular Herophili, explains lack of correlation between the severity of underlying pathology and infrequent clinical symptomatology.

- The higher areas of the cortex drain into the superior sagittal sinus (SSS) and the lower parts of the hemisphere into the transverse sinuses.

- Deep structures drain via a deep cerebral veins and eventually into the great cerebral vein.

- It eventually joins with the inferior sagittal sinus to form the straight sinus which drains into the left transverse sinus.

- Emissary veins from scalp, face, paranasal sinuses and ears, etc., diploic veins, and meningeal veins drain into cerebral venous sinuses either directly or via venous lacunae.

- Therefore CVT can occur as a complication of infective pathologies in the catchment areas, e.g., cavernous sinus thrombosis in the facial infections.

Aetiology

- CVT involves thrombosis of the intracranial veins and sinuses.

- It is an important cause of stroke that can be easily missed if not actively looked for.

- Venous thrombosis of the cerebral vessels may be due to localised infection e.g. mastoiditis or a systemic procoagulant condition.

- Venous thrombosis leads to increased venous pressure, oedema and venous infarction.

- Blood is forced out due to pressure rather than due to any vessel rupture.

- There is venous occlusion leading to back pressure but also reduced CSF drainage with increased ICP.

- Imaging has shown that there is both a degree of vasogenic and cytotoxic oedema.

| Risk Factors |

|---|

- Inherited Thrombophilia

- Hyperhomocystinaemia

- Antiphospholipid syndrome

- Factor V Leiden

- Prothrombin G20210 mutation

- Protein C/S deficiency

- Antithrombin II deficiency

- Oral Contraception

- Hyperviscosity/Polycythaemia

- Pregnancy / early post partum 6 weeks

- Nephrotic syndrome

- Meningitis / sinus infections

- Dehydration / Ecstasy

- Behcet's disease, SLE

- Localised mastoid, ear or sinus infections

- Underlying malignancy

- Idiopathic, L-asparaginase

|

Location

| Site | Frequency |

|---|

| Superior sagittal sinus | 72% |

| Lateral sinus (combined) | 70% |

| Straight sinus | 13% |

| Cavernous sinus | <10% |

| Note: CVT can sometimes occur as a cause of post LP headache. With a low-pressure headache patient feel better lying down. With CVT there is little difference, or the patient feels worse lying down. If you don't think of it you can't diagnose it. However CVT may also be the cause of the thunderclap headache for which you are doing the LP! |

Clinical Presentations

- Focal neurology e.g. hemiparesis due to stroke (ischaemic or haemorrhagic)

- Headache often localised,

- Headache is severe and dull and is worse when lying down or during Valsalva and may be thunderclap

- Raised ICP with papilloedema, coma and seizures, Encephalopathy with confusion

- Present with Idiopathic intracranial hypertension type picture with raised opening pressure on LP

- Jugular or lateral sinus clot can cause a pulsatile tinnitus

- TIA like episodes

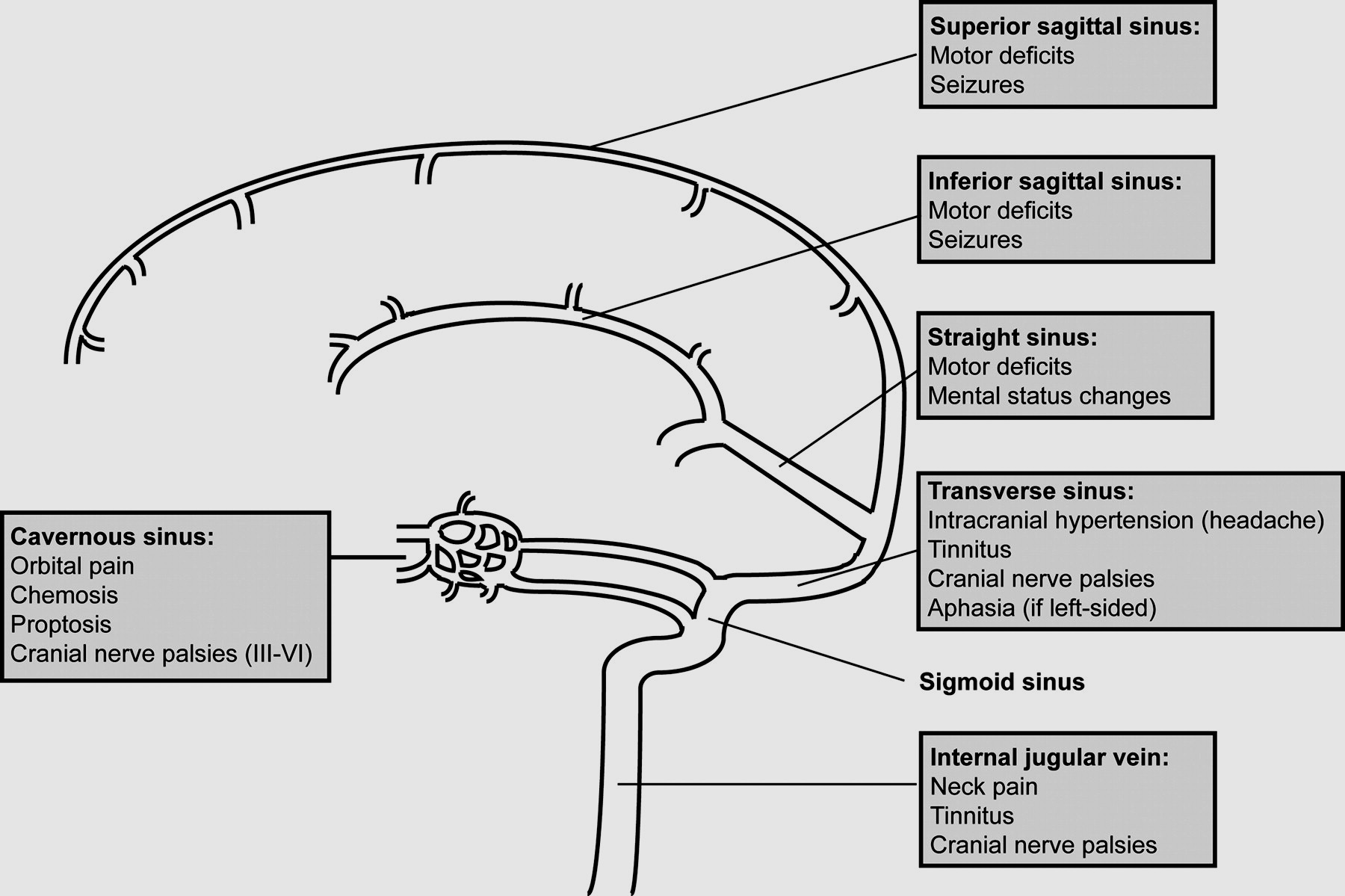

| Location | Clinical signs |

|---|

| Cavernous sinus thrombosis | Proptosis, chemosis, facial pain and headache, ophthalmoplegia, diplopia, ptosis, tenderness, febrile, can be bilateral, Impaired V1 sensation. Facial source of sepsis often staph Aureus needing antibiotics. |

| Super sagittal sinus thrombosis | Headache, papilloedema, seizures, motor/sensory deficits as per cortical ischaemia/infarction/haemorrhage |

| Transverse sinus thrombosis | Headache, hemiparesis, seizures, papilloedema, palsies of IX,X,XI |

| Note: Any presentation with headache and papilloedema and normal CT and raised CSF pressure the clinician should exclude CVT as the cause of the headache. |

Investigations

- Bloods:FBC, U&E, LFTs, ESR, CRP, Blood cultures, others - tumour markers etc as indicated: look for evidence of malignancy or infection/inflammatory disorders

- D-Dimer A positive test supports the diagnosis, but a negative test does not categorically exclude CVT and if clinical suspicion high then further imaging warranted. It is negative in 25% of cases.

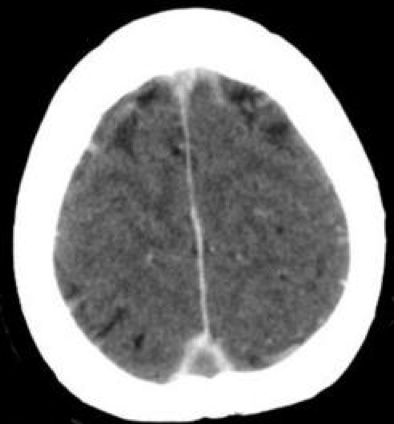

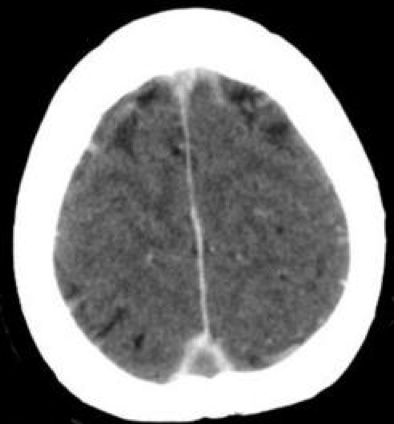

- Non contrast CT: May be normal or may show infarction or haemorrhagic infarcts and oedema not corresponding to a typical arterial territory. Thrombus can appear as hyperdense vein within the sinus for the first 1-2 weeks and this is a useful sign and may be called the cord sign on non-contrast CT due to fresh clot along falx. Subarachnoid blood may be seen. Clot may be seen in the superior sagittal sinus, Lateral sinuses, Straight sinus and Cavernous sinus but usually CTV/MRV is needed to confirm the diagnosis. Haemorrhage or infarction may be seen with a disproportionate amount of surrounding oedema.

- CT with contrast: may show a Empty delta sign is a CT sign of dural venous sinus thrombosis involving the superior sagittal sinus. Contrast outlines a triangular filling defect (thrombus). It is only seen when contrast is given with CT or MRI. There may be infarction, haemorrhage and often marked oedema.

- MRI with Gradient echo and MRV: MRV may show a filling defect. Can also show extent of infarcts, oedema, haemorrhage and evidence of venous thrombosis. Contrast enhanced MRV is better than time of flight MRV.

- DSA:This is the gold standard where there is uncertainty but increased costs and risk of complications. Useful where a Dural AV fistula suspected.

- CSF:: Not usually done but may be done as CVT may present as a thunderclap headache. May shows raised opening pressure and protein. LP may help reduce CSF pressure.

- Thrombophilia screen: should be done where an alternative explanation is not forthcoming. Testing is usually done several weeks after stopping anticoagulation. If abnormal results are found in assays for lupus anticoagulant, anticardiolipin, or anti-ß2 glycoprotein-I antibodies, then these should be repeated at least 3 months later, as the diagnosis of antiphospholipid syndrome is strengthened by two positive determinations of these biomarkers.

- Malignancy in older patients it might be reasonable when there is no alternative cause to exclude an occult malignancy with CT Chest abdomen pelvis, mammogram and tumour markers.

| Venous thrombosis of deep veins with infarction of thalami | Venous thrombosis with haemorrhage and oedema |

|---|

|  |

Cases with messages

| A 25-year-old polish girl presents to ED with severe headache. She is diagnosed as having a bad Migraine and no Imaging is done. Somehow the fact is missed that she has an inherited thrombophilia due possibly due to language issues. She presents 2 days later with hemiparesis and extensive venous infarction and oedema and is started on anticoagulation based on CT findings and history |

| A 56-year-old lady with breast cancer presents with headache and lateralising signs. CT shows extensive lobar haemorrhage and oedema and CTV confirms venous thrombosis. She is started on LMWH and gradually improves over 2 months and the haemorrhage and oedema settles. |

| A 62-year-old male is seen on the renal ward. He has nephrotic syndrome due to a glomerulonephritis. A CT scan shows a small lobar bleed with oedema. CTV confirms venous thrombosis. |

Complications

| Complications of CVST |

|---|

- Infarction may occur

- Deep and superficial Haemorrhage

- Subarachnoid bleeding

- Raised ICP and coma

- Acquired Dural AV fistula

- Coma, Death and Disability

|

CT with contrast showing Superior Sagittal Sinus thrombus with Empty Delta Sign. Note that the lateral sinus may be congenitally absent and reflects underlying anatomy rather than thrombosis. Anomalies of venous anatomy seen in 50%

Management

- Basics ABC and support. Management is as for DVT and involves immediate anticoagulation with Heparin (IV or LMWH S/C) even when there is haemorrhage which is more due to back pressure and diapedesis of red cells rather than damage to the structural integrity of the vessels. Patients may be monitored in neurology ITU with hyperventilation and sedation. Prognosis is worse with deep cerebral vein thrombosis as there is often bilateral thalamic venous infarction. Males and those with right lateral sinus thrombosis also do worse.

- Interventional neuroradiology:Direct IV microcatheter delivered thrombolysis has been given in selected cases whereby Interventional neuroradiologists can infuse catheter directed thrombolysis into the affected sinuses. Thrombectomy may be possible and even angioplasty and stenting in selected cases.

- Others:There is no indication for steroids having a benefit, even in patients with parenchymal lesions. Anticonvulsants are indicated for any seizure. Antibiotics for ear or facial infection or systemic infection as indicated.

- Anticoagulation: often starting with UFH or LMWH acutely even when there is haemorrhage. There may be a role for DOACs in the future. Then conversion to Warfarin which is given for 3-6 months followed by lifelong anti-platelets. Prolonged warfarin course for 12 months or even lifelong may be considered if idiopathic cause or an ongoing procoagulant condition.

- Surgery:In those with large infarcts or haematoma and raised ICP decompressive hemicraniectomy may be required and outcomes can be reasonable

References and further reading