Learning objectives

|

The National Institutes of Health Stroke Scale (NIHSS) is widely used as a standard tool to evaluate the severity of a patient's neurological deficit after a definite or suspected stroke. It was developed in 1983 by neurologists as a research tool and has developed into being an integral part of the stroke assessment and selection for acute therapies in the emergency department and on the stroke unit[1]. It has developed from being a pure research tool to being used to direct therapies and to detect changes in state in the clinical practice[2]. It has become an integral part of pre and post thrombolysis assessment. All patients with suspected stroke must have at least an initial assessment to meet the UK SSNAP targets suggesting that good centres assess and record NIHSS. It cannot be ignored. Its ubiquity reflects its utility. It is a quick, multifaceted, quantifiable and reproducible assessment of neurological dysfunction in stroke.

The NIHSS was designed around a traditional neurological examination [5] and examines consciousness, eye movements, visual field, facial palsy, motor strength, sensory function, coordination, language function, speech and neglect[1,6]. In the traditional version are 15 items [7] each one scoring separately with the total of the scale rating from 0, for unaffected patients, to 42 which is the worst probable score. Most stroke guidelines advocate thrombolysis for those with a score between 4 and 24 inclusive but there is some variability. Importantly a score of 0 does not mean a normal neurological examination as it does not pick up subtle neurology and for instance does not differentiate between an MRC rating of 4 or 5 for power both of which would be graded as 'Normal' or zero for each limb.

Stroke scales, including NIHSS, seek to quantify different aspects of function, to compare the baseline stroke severity of patient groups and to quantify neurological recovery over time. They also try to include monitoring of the neurological status for deterioration and try to adjust the final outcome for initial severity of stroke[3]. In order for the stroke scale to be a valid and useful tool a number of criteria should be fulfilled. The scale should be reliable, valid, sensitive, and easy to use and the items that compose the scale should be specific and prognostic for outcome [4].

The assessment is brief and can be performed within 8 minutes and can be repeated easily, it can be performed all hours in the ER, Stroke Unit or ITU, regardless if the patient is mute, ventilated or has limited mobility [8]. All type of care providers are able to effectively implemented the scale with a few hours of training as video training seems highly effective and that makes the scale reliable [9,10]. It can be assessed following training both by ED and Stroke physicians, nurses and other staff who have had formal training. Online NIHSS Certification is available for free through the American Stroke Association. The online program provides detailed instructions and demonstration scenarios for practice in scoring the NIHSS. Certification is completed by scoring different patient scenarios. (www.strokeassociation.org)[11]

In order to fill the NIHSS several principles should be followed. Items in the scale should be scored in the order listed. Performance in each category should be recorded after each subscale exam and it is best not to go back and change scores. Directions are provided for each exam technique and scores should reflect what the patient does, not what the clinician thinks the patient can do. The clinician should record answers while administering the exam and work quickly. Except where indicated, the patient should not be coached (i.e., repeated requests to patient to make a special effort) [11,12].

Here we shall go through the assessment with some clues. A typical NIHSS form is shown in the appendix. It is useful to develop some form of datasheet that allows repeated measurements for comparison. Unlike GCS higher scores a high score of 15 is good. With NIHSS a normal person should have a score of 0 and increasing value reflects increasing neurological deficit. One important caveat is that it quantifies significant dysfunction. A score of 0 does not exclude the diagnosis of stroke. The NIHSS is only a single part of the assessment process. Guidance suggests that the score should be done in the following order and you should score what you see and not what you expect. You should not go back and change earlier assessments unless a clear error has been made.

NIHSS apart from being a reliable scale is also a valid tool as it correlates with the infarct volume [6] and the outcome of the stroke. It provides more acuity than other outcome measures such as modified Rankin scoring. NIHSS has been used in a variety of clinical stroke trials to assess outcome measured at presentation, post thrombolysis and 24 hours, 7-day, 30 day and even 90 days post stroke. Two thirds of the patients with a NIHSS acute score of three or less will have an excellent outcome on the day 7, while very few patients with a baseline score of more than 15 will have an excellent outcome in three months [6]. Moreover if the baseline score is more than 16 there is a high probability of death or major disability [2].

NIHSS as a marker of deterioration.

Neurological and medical complications in patients with stroke, which are frequent, are also related to poor clinical outcome. Increased baseline NIHSS has been associated with an increased risk of complication during hospitalisation1. Thus, NIHSS is a useful tool to predict neurological and medical complication in a stroke patient and can be used to alert physicians in order to expect possible risks and be able to make early decisions about further surveillance and management.

NIHSS benefits from being reliable, valid and a sensitive tool for neurological deterioration and stroke outcome.

The NIHSS can be used by different care providers and makes it easy to communicate the neurological deficit with other physicians and saves time on the decision for the patient's management [6]. NIHSS is also sensitive for research and can apply to medical records for analysis [6]. As all scales though, NIHSS has its limitations that should be considered in order to ensure that it is used and interpreted appropriately.

The outcome of a stroke does not correlate only with the infarct volume but also with location. The NIHSS detects weakness and sensory loss which can be bilateral or either anterior or posterior circulation as can hemianopia. Also NIHSS seems make discrimination between dominant and no dominant hemisphere. In the scale, 7 of the 42 points are related to the language function, whereas only 2 of the 42 points are attributed to neglect functions.

As a result, the scale seems to favour left/dominant hemisphere strokes, with infarction volume of right hemispheric events being consistently larger than left hemispheric ones for patients with the same NIHSS score [2,6,14]. However, language is hugely important and dysphasia is a huge disability and needs recognised to reach the threshold for acute therapies if other modalities are unimpaired.

The NIHSS can detect brainstem specific palsies such as III, IV and VI which are scored within Gaze as well as hemianopia which may be due to posterior cerebral artery involvement. Limb ataxia is assessed and useful for detecting cerebellar signs, but truncal ataxia is not assessed. If the NIHSS is seen as a tool for treatment selection then there are sufficient points available to reach the thrombolysis threshold of 4 if there is dysarthria, ataxia and gaze palsy but these may be subtle, undetected or absent and thrombolysis may be declined. There are no specific points for diplopia or Horner's syndrome, truncal ataxia or dysphagia, deafness or vertigo and nystagmus. A low pick up on posterior circulation strokes is one of the main limitations of the scale and there is poor correlation with NIHSS score in patients with posterior circulation infarction [1,13]. Relatively low scores, even zero, can occur in patients with disabling infarctions of the brainstem and the cerebellum [1,6,15]. Importantly a patient with a significant cerebellar infarct or lateral medullary syndrome may score only 2-4 points and may therefore not be considered for acute therapies despite the fact that these infarcts can be disabling and occasionally life threatening [6]. Moreover, the scale does not include a detailed assessment for the cranial nerves [6].

In mitigation the highest scores will be obtained for those with dominant hemispheric strokes with aphasia, weakness, sensory loss and hemianopia and dysarthria which does match with the disability and these are much commoner strokes and have the poorest prognosis. In these patients the NIHSS score quickly reaches and even exceeds that for therapies such as thrombolysis suggesting that points could be shifted posteriorly to redress the balance. It perhaps underscores the point that clinicians must assess the potential of lasting disability with each patient and there are occasional circumstances when it is appropriate to ignore the NIHSS.

Practical difficulties in assessment include the ceiling effect. Ataxia, sensory loss, inattention, and visual fields, in order to be assessed, require a considerable degree of comprehension on the part of the patient and often are not assessable [5]. As not assessable items must score zero and in practice there is a scoring ceiling which is well below the maximum of the scale [3,5]. The reliability of each item that compose the NIHSS has been studied extensively. The items rating facial palsy, limb ataxia and language are consistently variable and less reliable [7,9] and this is one of the reasons that systemic training before applying the scale is favourable [10]. Last but not least is that NIHSS applies to the neurological deficit, but not to the actual cause of the signs. It cannot help in the differential diagnosis and in a suspected stroke the complete history, the neurological examination and the neuroimaging are needed to exclude other conditions that can mimic a stroke [6].

There is no ideal stroke scale and there is always room for improvement. However, NIHSS is an improvement over the scales that have been used over the years [2]. It is valid, reliable, sufficiently accurate, involves more aspects than just motor function including items for posterior circulation infarcts and tries to measure the disability. That means that requires scoring greater number of aspects, but video training is easily accessible and provides standard of the use and reliability [3] . This is why the NIHSS is an attractive clinical deficit scale for the evaluation of stroke patient in a trial setting and beyond and is a tool which all stroke physicians should be fluent with aware of its strengths and limitations.

The NIHSS should be included and available in all acute stroke assessment proformas and recorded. There are also a number of applications for mobile devices that enable rapid inputting and assessment of the NIHSS but this must go along with a clear understanding of who to perform the assessment.

Introduction

Practical Aspects

NIHSS Actual Assessment 1. Level of Consciousness: Consciousness is only really impaired in acute stroke if there is a massive supratentorial event such as infarction with oedema, bleeding or hydrocephalus or diencephalic (mainly bilateral thalamic involvement) or other brainstem neurology or seizure or toxic-metabolic causes. Various theories used to explain reduced level of consciousness involve interaction of the cortex and the reticular system. The natural state post stroke in most patients is for things to improve. Any increase in the NIHSS much as with decreases in GCS needs immediate reassessment and consideration for repeated imaging. For example below if the 1a consciousness level were to change from a 0 to a 1 then we would in the setting of a large MCA infarct in an appropriate patient be considering this patient for transfer to a neurosurgical centre to manage their potential malignant MCA syndrome with hemicraniectomy. In a post thrombolysis patient, it may signify haemorrhage or aspiration and infection. Consciousness is assessed in three ways - motor response, two simple questions and assessing the ability to follow two one-step commands. The questions check cognition as well as consciousness and may be impaired in delirium or dementias as well as in obtunded patients.

1a Level of Consciousness.

1 b Level of Consciousness Questions: Next simply and clearly ask the patient to state their month and their age. A point is given for each answer given incorrectly. The first response is recorded as to whether it is correct or not. Repeated questioning or multiple attempts are not allowed. It tests both consciousness and speech.

1c. Level of Consciousness Commands: The patient is asked to do two actions, the first to "open and close the eyes" and then to "make a fist and open it". The patient should use the non-affected hand. This is a test of motor function and cognition. If dysphasic or confused or hard of hearing the examiner can give a visual demonstration to show the patient the actions needed to copy. It is reasonable to use another one step command if for some reason the hands cannot be used. The assessment is for consciousness and responsiveness and so credit is given if an unequivocal attempt is made but not completed due to weakness. If patient does not respond to command, the task should be demonstrated.

2. Best Gaze: This test evaluates ability of the patient to move the eyes side to side on command and is done from the bedside. Stroke patients with large cortical lesion tend to have a contralateral hemianopia to the lesion and look away from it 'to the side of the lesion'. Only horizontal eye movements are tested. Simply with a left hand on the patient's head to keep it stationary ask the patient to follow your finger from one side across the midline to the other side. This can test patients with large hemispheric strokes where gaze can be fixed towards the 'unaffected side'. It is important to differentiate from those who have a IIIrd nerve palsy with ptosis and down and out pupil, and IV and VI nerve weakness with failure to abduct and these are scored with 1. If gaze is fixed towards the 'affected side' then an irritative focus and seizure should be suspected especially if there are any features and the test reassessed once controlled. If the patient is aphasic or confused try and get them to focus and track on a moving object such as a finger or pen or light source or the examiner with eye contact moving from one side to the patient to the other and seeing if the eyes follow. A blind patient can simply be asked to look left and right.

3. Visual fields: A cortical lesion involving optic radiations in the anterior or posterior circulation will give a contralateral hemianopia which may be partial with upper or lower quadrants preserved. Damage to Lower temporal fibres will cause a superior quadrantanopia and parietal fibres an inferior quadrantanopia. Test upper and lower quadrants by confrontation, using finger counting or visual threat, as appropriate. If the patient sees moving fingers in all quadrants, this can be scored as normal. Patients may be aphasic but if they look to the appropriate side of the moving fingers, this can be scored as an intact visual field and normal. If there is unilateral blindness or enucleation, visual fields in the remaining eye are scored.

4. Facial Palsy: Next assess the muscles of facial expression supplied by the facial nerve. Facial weakness is usually due to a lesion in the contralateral primary motor cortex or the descending corticobulbar fibres which cross the midline in the pons to the VII nucleus. There is bilateral cortical representation of the upper face so this should be relatively unaffected and eyebrow raising should be broadly symmetrical. Ask - or use non-verbal mimicry to encourage the dysphasic patient to show teeth or raise eyebrows and close eyes. Use a noxious stimulus e.g. sternal rub to elicit a grimace in the poorly responsive or non-comprehending patient. If facial trauma/bandages, orotracheal tube, tape or other physical barriers obscure the face, these should be removed to the extent possible.

5. Motor Arm: Motor weakness is due to damage to the contralateral motor cortex or its descending corticospinal tract. As the patient to hold arms out with the pronated with palms down to 90 degrees (if sitting) or 45 degrees (if supine). Note the typical supine positioned arm to look for pronator drift is not used and this is purely an assessment of weakness. Pronator drift as a useful clinical signs is not assessed. Test each limb in turn, beginning with the stronger arm and palm down. Demonstrate the activity to the aphasic patient and use urgency in the voice and pantomime to encourage effort. Do not use noxious stimulation. In the case of amputation or joint fusion at the shoulder, the examiner should record the score as untestable (UN), and clearly write the explanation for this choice.

6. Motor Leg: Motor weakness is due to damage to the contralateral motor cortex or its descending corticospinal tract. Leg weakness is represented on the medial surface of the primary motor cortex supplied by the anterior cerebral artery. Ask the patient to hold the leg at 30 degrees to the horizontal (always tested lying supine). Test the unaffected leg first. Drift is scored if the leg falls before 5 seconds. The aphasic patient is encouraged using demonstration and urgency in the voice, but not noxious stimulation.

7. Limb Ataxia: This item is aimed at finding evidence of a stroke affecting the ipsilateral cerebellum and its brainstem and related connections. Test with eyes open. If there is a hemianopia ensure that it is done within the area of intact vision field. In case of blindness, test by having the patient touch nose from extended arm position. Otherwise the traditional finger-nose-finger and heel-shin tests are performed on both sides in arm and leg. Test the presumed unaffected side first. Make allowances for limb weakness when testing. Check all four limbs separately.

8. Sensory: Sensation is tested bilaterally on face, arm (not hand), trunk and leg by pinprick with verbal response or withdrawal from noxious stimulus in the obtunded or aphasic patient. Sensation travels across the midline to the contralateral thalamus and is appreciated in the parietal primary sensory cortex. Only sensory loss attributed to stroke is scored as abnormal - a distal peripheral neuropathy in a diabetic may be ignored. The examiner should test as many body areas (arms - not hands, legs, trunk, face) as needed to accurately check for hemisensory loss and comparison should be made between location on both sides.

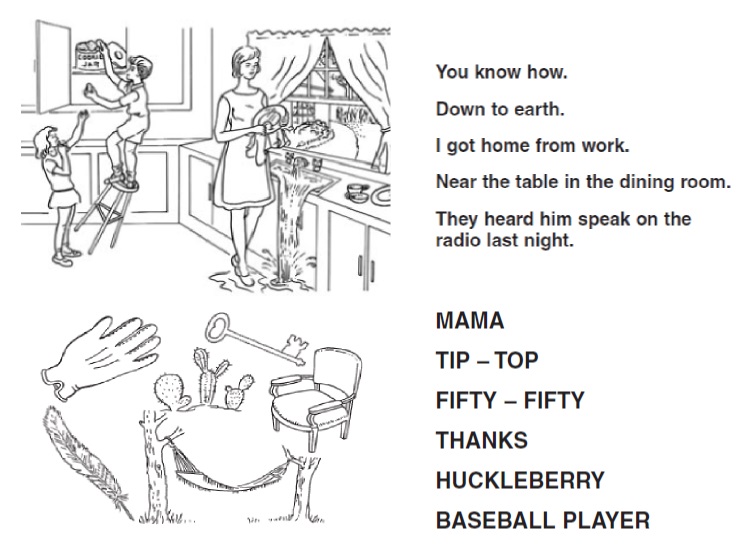

9. Best language: A great deal of information about language and comprehension will be obtained while the preceding history taking and examination. For this scale item, the patient is asked to describe "what is happening in the attached picture", to "name the items on the attached naming sheet" and to "read from the attached list of sentences". Intubated patients can be assessed by writing. This is again an assessment of dominant hemispheric areas and can be damaged with strokes affecting speech areas and their connections on the dominant side. Give patients adequate time. If visual loss interferes with the tests, ask the patient to identify objects placed in the hand, repeat and produce speech. The patient in a coma (item 1a=3) will automatically score 3 on this item. The examiner must choose a score for the patient with stupor or limited cooperation, but a score of 3 should be used only if the patient is mute and follows no one-step commands.

10. Dysarthria: Dysarthria is due to damage to the ipsilateral lower motor neuron cranial nerves or lesions of the contralateral motor cortex and corticobulbar fibres. If patient is thought to be normal, an adequate sample of speech must be obtained by asking patient to read or repeat words from the attached list. If the patient has a severe aphasia, the clarity of articulation of spontaneous speech alone can be rated. Only if the patient is intubated or has other physical barriers to producing speech, the examiner should record the score as untestable (UN).

11. Extinction and Inattention (formerly Neglect): Assessments of symmetrical vision and sensation are made. Neglect is shown when testing for touch sensation and vision in which symmetrical simultaneous stimuli are ignored but awareness is present when tested unilaterally. If the patient has a severe visual loss preventing visual double simultaneous stimulation, and the cutaneous stimuli are normal, the score is normal. If the patient has aphasia but does appear to attend to both sides, the score is normal. The presence of visual spatial neglect or anosognosia may also be taken as evidence of abnormality. Since the abnormality is scored only if present, the item is never untestable. 0 =

Prognostic Uses

Bias Towards the Dominant Cortex

Underrepresenting the Posterior Circulation

Next: >> Bamford / Oxfordshire Community Stroke Project Classification

References