Learning objectives

|

| Patients with visual loss of vascular aetiology such as Transient monocular blindness, CRAO, or BRAO may have up to 19.5% risk of concurrent ischaemic stroke, even when there are no other neurological deficits. These strokes were detected acutely with brain MRI using DWI but were missed on CT. They should be rapidly seen in a TIA clinic. [6] |

Introduction

The optic nerve is an extension of the central nervous system and shares a similar vascular supply. There are a number of ophthalmic vascular syndromes to be aware of. There are links here to other useful pages which are Migraine which is a common cause of recurring transient visual symptoms which may extend beyond the eye and also Giant cell arteritis/Temporal arteritis a vasculitis affecting the blood supply to the optic nerve which needs rapid diagnosis and treatment. One intermittent error is the misdiagnosis of a hemianopia as an ocular problem by the inexperienced. Testing by confrontation or formal visual field testing quickly clarifies this. A homonymous hemianopia is due to a destructive hemispheric lesion which may be stroke or an alternative cause and requires urgent brain imaging.

Vascular Physiology of the Eye

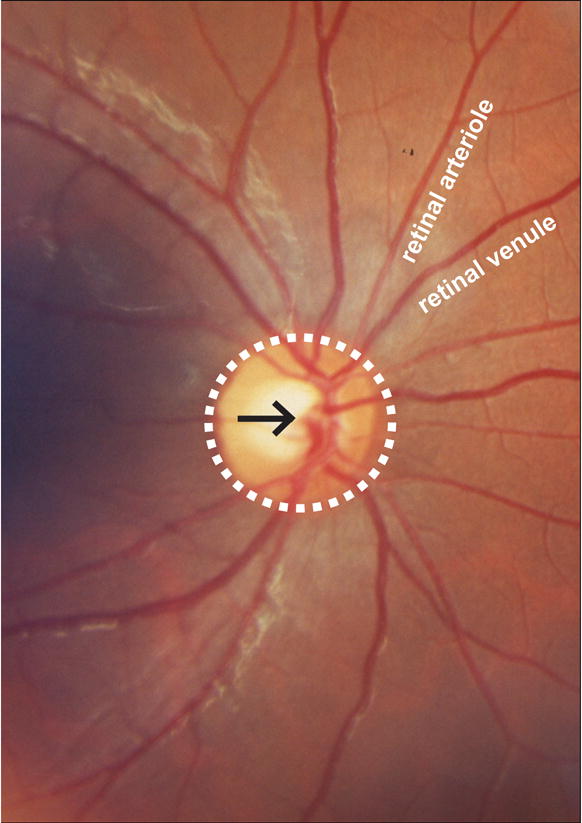

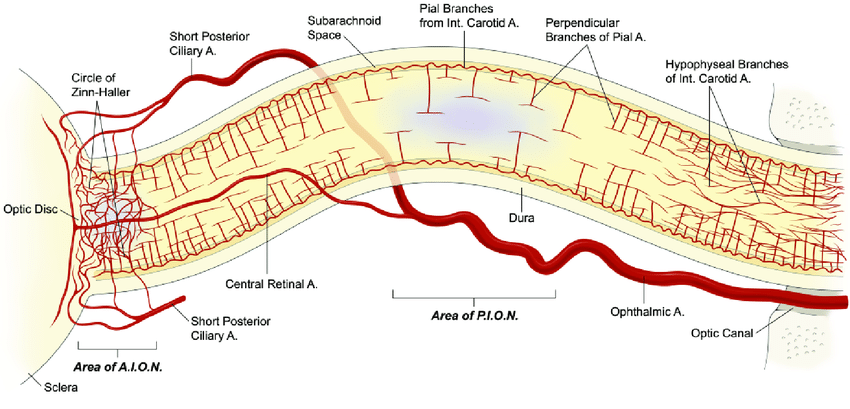

Vision requires the proper functioning of rod and cone cells that require a steady supply of ATP. Any compromise to supply will cause a visual impairment which may be global or focal. Anyone who has fainted will recall the transient general dimming in vision that precedes syncope. The eye is supplied by branches of the ophthalmic artery. The ophthalmic artery is the first branch of the internal carotid artery. The ophthalmic artery gives off a branch which pierces the nerve and forms the central retinal artery which goes to supply the inner retina. The nerve itself is supplied by small pial penetrating branches of the posterior ciliary artery, another branch of the ophthalmic artery.

| Vascular supply to the eye |

|---|

|

The retinal circulation is unique compared to other vascular beds in the human body in that it does not have autonomic innervation, and therefore is controlled by local and circulating factors such as local metabolic demands, blood pressure, oxygen and carbon dioxide levels. It can therefore be a marker of low blood pressure but then symptoms would be bilateral. The fractional oxygen extraction in the retinal circulation is high. In contrast, the majority of the blood supply to the retina is carried via the posterior ciliary arteries to the choroidal circulation, which supplies the retinal pigment epithelium and outer sensory retina. It has a comparatively low oxygen extraction fraction [1].

Clinical Syndromes

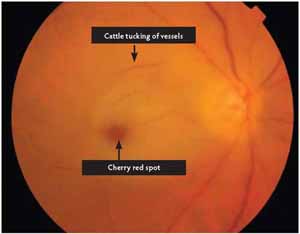

All patients with a visual problem should be seen first urgently at the Eye emergency service and then referred to the TIA clinic or back to primary care. Acute retinal arterial ischaemia, which includes transient monocular blindness (TMB), branch retinal artery occlusion (BRAO), central retinal artery occlusion (CRAO) and ophthalmic artery occlusion (OAO), is most commonly the consequence of an embolic phenomenon from the ipsilateral carotid artery, heart or aortic arch, leading to partial or complete occlusion of the central retinal artery (CRA) or its branches [3]. These patients should be seen in TIA clinic for investigations.

Transient monocular blindness or visual loss is caused by transient occlusion of the CRA or its branches and causes unilateral vision loss typically lasting several minutes, followed by spontaneous recovery of vision without detectable permanent functional visual deficits. BRAO and CRAO are caused by longer-lasting partial or complete occlusion of the CRA or its branches, leading to permanent visual dysfunction [decreased visual acuity and/or visual field deficits]. Typically, CRAO produces severe visual dysfunction (very poor visual acuity and/or severely constricted visual field), while BRAO produces less severe visual dysfunction.

The cilioretinal artery, which is present in 15-30% of the population, originates from the posterior ciliary circulation, not the CRA. Therefore, the cilioretinal artery is not affected in CRAO and central visual acuity can be near normal if the cilioretinal artery supplies part of the macula and the fovea. However, the affected eye will have severely impaired peripheral vision [3].

| Questions to ask regarding transient monocular vision loss [5] | |

|---|---|

|

| Differential of transient monocular vision loss | |

|---|---|

|

|  |

|

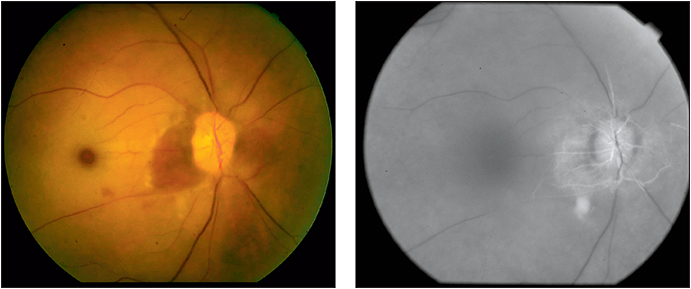

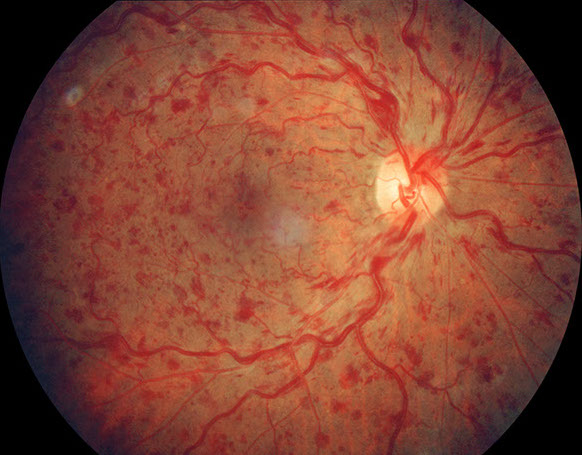

Central/Branch Retinal Vein Occlusion

CRVO is a condition where there is venous obstruction to the retinal venous system. This can result in a sudden painless reduction in visual acuity which may be total or related to a visual field. There may be retinal ischaemia. It can involve the central vein or its branches. Risk factors include glaucoma, hypertension, diabetes mellitus, hyperlipidemia, hyperhomocysteinemia, coagulation disorders, and rarely systemic inflammatory conditions such as Behcet's syndrome, PAN or Sarcoid. Diagnosis is based on history and fundal exam which can show Optic disk oedema, Macular oedema, dilated and tortuous retinal veins proximal to the obstruction. There may be widespread deep and superficial haemorrhages (dot-blot and flame-shaped) as well as cotton-wool spots an even neovascularisation in advanced cases. Fluorescein angiography can identify the site and presence of macular oedema and any neovascularization. Fundal findings may be regional or global. Management includes intravitreal corticosteroids, intravitreal anti-vascular endothelial growth factor agents, and laser photocoagulation. Those with non-ischaemic (well-perfused) CRVO and good visual acuity on presentation (better than 20/40, corrected), have a more favourable prognosis. There is no need for a stroke team referral. There is no doubt that those with CRVO are at increased risk of stroke. People with RVO are at a significantly greater risk of developing stroke, ischaemic stroke, and haemorrhagic stroke. However, RVO does not significantly increase the risk of all-cause mortality [2]. However the relevant vascular risk factors can be dealt detected and dealt with by ophthalmology and primary care.

|  |

Ocular Ischaemic Syndrome

Rare condition characterized by transient vision loss due to retinal ischaemia resulting from occlusion in either the common or internal carotid artery. Patient experiences loss of vision and Fundoscopy shows dilated, irregular retinal veins and sometimes retinal haemorrhages. Patients may present with dull or aching ocular or periorbital pain due to underlying ischaemia. Dilated veins are not tortuous. Fundal haemorrhages typically are at the midperiphery and there is no disk oedema, whereas disk oedema is characteristic in central retinal vein occlusion and present sometimes in branch retinal vein occlusion. Definitive diagnosis is made via Doppler ultrasonography or carotid angiography.

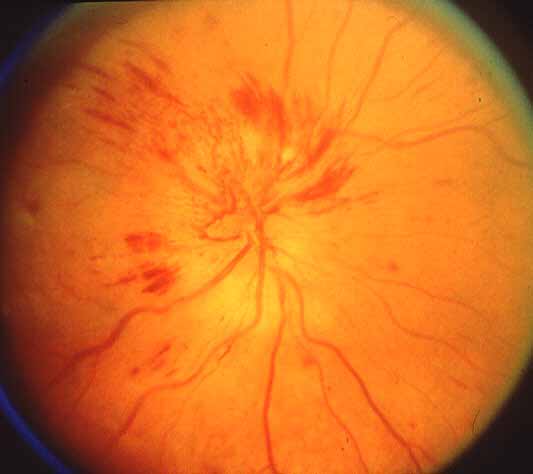

Non Arteritic Anterior Ischaemic Optic Neuropathy

Anterior ischaemic optic neuropathy (AION) is due to ischaemic damage to the optic nerve head as it enters the retina which causes disc swelling. If the ischaemic damage is more proximal in the nerve there is no optic disc swelling and it is termed a Posterior ischaemic optic neuropathy. Anterior ischaemic optic neuropathy causes a loss of vision due to infarction of the optic nerve. The patient may have a mild to severe visual loss which is often altitudinal so that superior and inferior half fields are gone, field defects and a pale swollen optic disc. It can often be noted on waking. With AION the Fundus shows a pale optic disc with swelling, there may be flame haemorrhages on the swollen disc or nearby neuroretinal layer, and sometimes with nearby cotton-wool exudates. The visual loss comes on suddenly acutely but may progress over days. It may be permanent but some can improve over weeks or months. It is though that the vessels affected are the posterior ciliary arteries which feed the head of the optic nerve. One cause is Giant cell arteritis / Temporal arteritis and this should be looked for as an eye emergency. In others the cause is simply microvascular disease. AION seems commoner in those with a small to disc ration of the optic disc presumably as the fibres are bunched tighter. Risks factors include Hypertension, atherosclerosis, Sleep apnoea, Diabetes mellitus, migraine and Carotid disease and local causes such as venous outflow obstruction or elevated intraocular pressure or anaemia or BP drop. The differential includes CRVO and Papilloedema and optic disc drusen.

|  |

Disc swelling and microhaemorrhages

Arteritic Anterior Ischaemic Optic Neuropathy

Please see article on Giant cell arteritis/Temporal arteritis which is the commonest cause. Others include Polyarteritis nodosa and SLE. There is usually evidence of a vasculitis with raised CRP and ESR and systemic features. It tends to be a more extensive and severe than the non arteritic form. Indeed it can go on to affect the other eye if untreated. Visual loss with GCA (Arteritic Ischaemic Optic Neuropathy) is usually worse. Some texts quote GCA as causing episodes of amaurosis before blindness which appears not to be a feature of Non-arteritic AION.

Investigations

- Ophthalmologist : Slit lamp examination of eye. Assessment of visual acuity. Field testing may be done. Fluorescein Angiography which involves giving a yellow dye through an IV in the arm, and a camera is set up to take images of the blood vessels in one or both eyes over several minutes.

- Stroke work up: FBC, HbA1C, Lipids, ECG, 24 hr tape. Echo where suspicion of cardiac disease.

- Carotid duplex to look for ipsilateral disease

- Erythrocyte sedimentation rate and C-reactive protein are necessary in patients older than 50 years to screen for inflammation, which may suggest giant cell arteritis. if there is a very high suspicion despite normal inflammatory markers a temporal artery biopsy should be performed.

- MRI DWI may show ipsilateral embolic strokes supporting an unclear diagnosis. However if asymptomatic and a diagnosis of embolic disease suspected it may not alter management. A CT Scan may be considered where MRI not possible but unlikely to have the acuity to detect small embolic events.

Management

- Patients with suspected embolic eye disease should be referred immediately to stroke physicians through established pathways. As disease is uniformly ischaemic an antiplatelet either Aspirin or Clopidogrel should be commenced

- TIA clinic assessment should include a focus on causality. Carotid duplex should be performed as well as a basic embolic stroke work up however the evidence show sthat those with carotid stenosis and Amaurosis have a much lower risk of stroke than those with hemispheric symptoms. The three-year risk of ipsilateral stroke was lower and the strokes less disabling among patients who presented with transient monocular blindness than among those who presented with hemispheric attacks. The perioperative rate of stroke and death was also lower among patients with monocular blindness. The frequency and duration of monocular ischaemic attacks bore no relation to the risk of stroke. [7].

- Best medical therapy includes Antiplatelets, Lipid lowering agent and management of risk factors such as blood pressure, smoking, diabetes etc. Those with AF/PAF need anticoagulation.

- Suspected Retinal vasospasm with repeated stereotypical attacks may be treated with calcium channel blockers. They do not leave any permanent vision changes, but can be frightening.

- Non Arteritic Anterior Ischaemic Optic Neuropathy need to see primary care physician to manage vascular risks factors such as BP and diabetes. They don't need referral to stroke physicians or neurologists.

References and further reading

- [1]: Retinal vascular changes are a marker for cerebral vascular diseases. Curr Neurol Neurosci Rep. 2015 Jul; 15(7): 40.

- [2]: Risk of Ischemic Stroke, Hemorrhagic Stroke, and All-Cause Mortality in Retinal Vein Occlusion: A Nationwide Population-Based Cohort Study. J Ophthalmol. 2018; 2018: 8629429.

- [3]: Acute retinal arterial ischemia.Ann Eye Sci. 2018 Jun; 3: 28.

- [4]: Management of Acute Retinal Ischemia. Ophthalmology 2018;125:1597-1607

- [5]: Update on the evaluation of transient vision loss. Clin Ophthalmol. 2016; 10: 297-303.

- [6]: Risk of Acute Ischemic Stroke in Patients With Monocular Vision Loss of Vascular Etiology. Journal of Neuro-Ophthalmology: September 2018;38:328-333

- [7]: Prognosis after transient monocular blindness associated with carotid-artery stenosis. N Engl J Med 2001;345:1084-1090.

| Note: The plan is to keep the website free through donations and advertisers that do not present any conflicts of interest. I am keen to advertise courses and conferences. If you have found the site useful or have any constructive comments please write to me at drokane (at) gmail.com. I keep a list of patrons to whom I am indebted who have contributed. If you would like to advertise a course or conference then please contact me directly for costs and to discuss a sponsored link from this site. |