Introduction

Atrial fibrillation is an atrial arrhythmia where the atria shows chaotic and disorganised electrical activity resulting in loss of normal atrial systole. It is associated with formation of thrombosis within the atrial appendage which can break off and embolise. The brain has a high flow rate for its volume and is a high risk target for embolism. Atrial fibrillation per sae is not a fixed risk. Risk requires the arrhythmia plus a set of confounding risk factors which dramatically increase the risk of cardioembolic stroke. Why not all AF is equal is an interesting topic yet to be explained. The risks are well set out in scoring systems such as CHADS2 and CHADS-VASC seen below. Generally anyone with TIA and Stroke and AF benefits from anticoagulation unless there are significant bleed risks.

AF occurs due to structural and/or electrophysiological changes to atrial tissue that promote the characteristic abnormal impulse formation and/or propagation. The list of causes is broad from excessive T4 to chronic hypertension or infiltrative diseases or acute infection. There are a whole plethora of intrinsic and extrinsic factors for which the final common pathway is the generation of AF. Once AF begins it seems to be self sustaining and "AF begets AF".

A lot of consideration is looking at whether AF is causative or associative with stroke. Those with AF have a 3-5 fold increased risk of stroke. A causal link is easily explained through the atrial stasis and thrombus formation pathway. For some the link is less clear and other factors come into play. AF however seems to be commoner with lacunar strokes. Those with AF also have twice as much large artery atherosclerosis. A good review article on AF and mechanisms is found here. Atrial fibrillation accounts for ≥15% of all strokes in the United States, 36% of strokes for individuals aged >80, and up to 20% of cryptogenic strokes. The incidence of AF in those over 85 is over 10%.

ECG appearance

The ECG appearance below shows the undulating irregular baseline and the random RR variation of QRS complex which generates the irregularly irregular pulse

Clinical Effects of Atrial Fibrillation

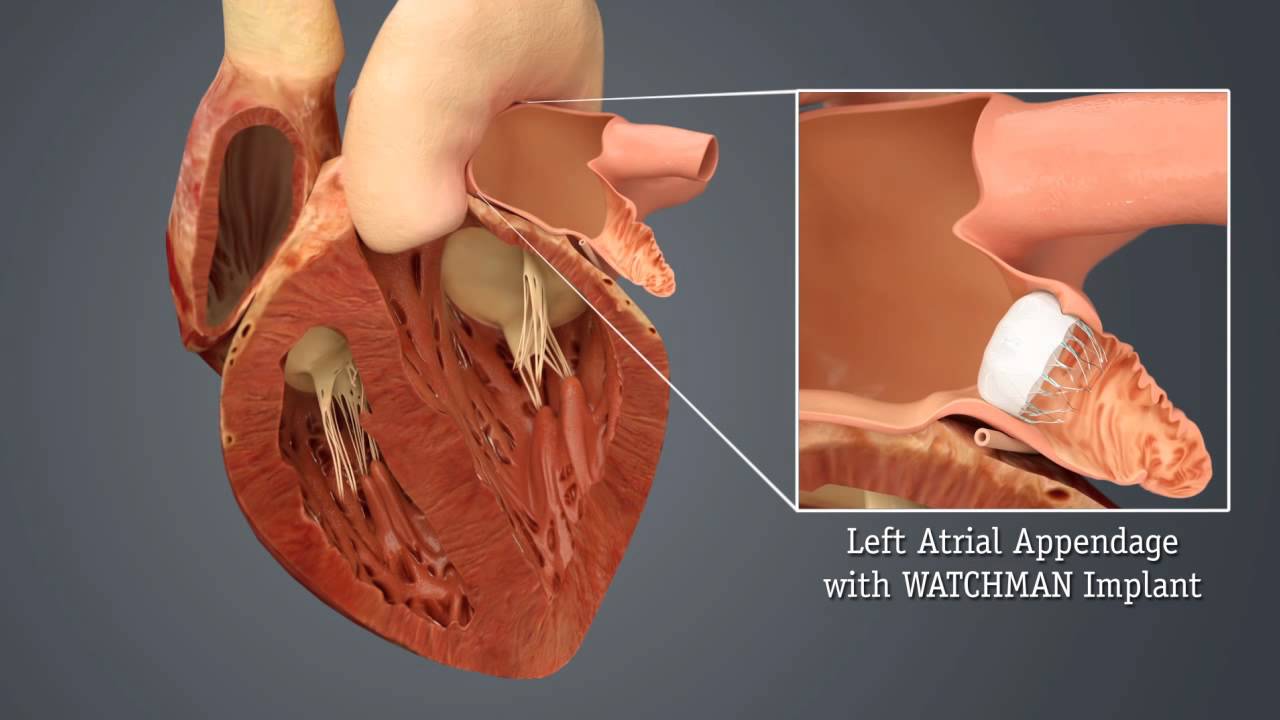

The effects of AF are not just cardio-embolism but fatigue, worsening heart failure, palpitations and reduced mortality and morbidity much of which is allied to the underlying cause. Atrial fibrillation is extremely common in those over the age of 65. In terms of stroke risk patients should be divided into those with or without mitral valve disease mainly stenosis. These are the so called valvular AF with a very high risk of embolic phenomena and stroke. The risk of stroke is at least six times higher in patients with atrial fibrillation than in healthy controls. The loss of atrial systole in atrial fibrillation leads to stasis and thrombosis most marked within the left atrial appendage.

The left atrial appendage is an embryonic remnant of the original left atrium. It is a long, tubular, trabeculated structure, in continuity with the left atrial cavity. Its unique anatomy predisposes to in-situ thrombus formation, and more than 90% of atrial thrombi in patients with non-valvular atrial fibrillation are believed to originate in the left atrial appendage. [McCabe DJH et al.2009]

| Clinical Effect of AF | Points |

|---|---|

| Death | Usually doubled in incidence < 48 hrs and is reduced by antithrombotic therapy |

| Stroke | Increase in Ischaemic and haemorrhagic stroke and more severe |

| Admissions | Increased risk of hospital admission |

| Quality of life | Wide variation from no impact to severe |

| LV function | Wide variation from a tachycardiomyopathy to no effect on LV |

Atrial fibrillation can come in several different forms as shown in the table below.

| Type AF | Definition |

|---|---|

| Paroxysmal AF | Usually lasts < 48 hrs though others define 7 days and may terminate spontaneously. Can recur with variable frequency |

| Persistent AF | Continuous and Lasts > 7 days or requires Cardioversion |

| Long standing Persistent AF | Lasts > 12 months |

| Permanent AF | Accepted and all attempts at cardioversion or rhythm control have ceased |

| Silent AF | High degree of suspicion by pattern of stroke and risk factors but to date undocumented PAF |

| Non valvular AF | AF but no rheumatic mitral stenosis, no mechanical or bioprosthetic heart valve or mitral valve repair |

Valvular Atrial Fibrillation

Valvular heart disease tends to infer the presence of rheumatic mitral stenosis which is the most common lesion associated with thromboembolism, irrespective of the coexistence of mitral regurgitation. Atrial fibrillation develops as MS progresses and increases the risk of thromboembolism up to 18 times. Thrombi associated with mitral stenosis can be found on the atrial wall or in the left atrial appendage. Risks of embolic stroke in these patients is related to age and low cardiac output, but not left atrial size, mitral calcification, or severity of mitral stenosis. The association of mitral regurgitation with thromboembolism correlates with the coexistence of mitral stenosis.

Oral anticoagulation reduces risk of stroke in patients with rheumatic mitral stenosis, particularly those with coexistent atrial fibrillation. The risk-benefit ratio in those without atrial fibrillation is not known. Of those patients who have had one event, early recurrent embolism has been reported in up to two thirds and aggressive anticoagulation instituted with Warfarin. The newer agents such as Dabigatran have not been licensed for use in this group of patients and either Warfarin or LMWH is needed long term.

Non Valvular Atrial Fibrillation

This is defined above as those with AF but no rheumatic mitral stenosis, no mechanical or bioprosthetic heart valve or mitral valve repair and this definition is used in the AHA/ACC guidelines listed below. For these patients the CHA2DS2-VASc score is recommended for assessment of stroke risk.

So there are some patients with AF who are at a very low risk of cardioembolism. Where the stroke risk is less than 1% Warfarin is not advocated and aspirin is possibly a reasonable choice. In an attempt to improve risk assessment the CHADS2 score has been very helpful and has been improved upon with the CHADS2-vasc score [Lip GY et al. 2010, Olesen JB 2011].

The score is useful for assessing risk, giving a more personalised risk assessment to patients and communicating risk and beneficial strategies. However the risk of anticoagulation related bleeds must balance the reduction in embolic episodes. The HAS-BLED score has been shown to be useful.

| Clinical Finding in CHADS2-vasc score | Points |

|---|---|

| Heart failure or EF < 35% | +1 |

| Hypertension | +1 |

| Age | 65-74 +1 over 75 + 2 |

| Diabetes | +1 |

| Stroke, TIA, Systemic Embolism | +2 |

| Vascular disease, previous MI, aortic plaque | +1 |

| Sex | Female +1 |

CHADS2VASC Score

| CHADS2VASC Score | Yearly risk of stroke without warfarin (or equivalent) | Management |

|---|---|---|

| 0 | 0% | Regard as truly low risk so that no antithrombotic therapy is preferred |

| 1 | 1.3% | Warfarin or DOAC. may consider as low risk if only risk is female, under 65 and lone AF |

| 2 | 2.2% | Warfarin or DOAC |

| 3 | 3.2% | Warfarin or DOAC |

| 4 | 4.0% | Warfarin or DOAC |

| 5 | 6.7% | Warfarin or DOAC |

| 6 | 9.8% | Warfarin or DOAC |

| 7 | 9.6% | Warfarin or DOAC |

| 8 | 6.7% | Warfarin or DOAC |

| 9 | 15.2% | Warfarin or DOAC |

For patients with non-valvular AF and a CHA2DS2-VASc score of 0, it is reasonable to omit antithrombotic therapy. For patients with non-valvular AF with prior stroke, transient ischaemic attack (TIA), or a CHA2DS2-VASc score of 2 or greater, oral anticoagulants are recommended.

However one has to balance this with bleeding risk which can be quantified to some extent by the HAS-BLED criteria shown below. Interestingly the risks of bleeding often are similar to those of risks of ischaemic cardioembolic stroke e.g. stroke, blood pressure and age. It is a delicate balance but most of us would favour anticoagulation and to manage any risks of bleeding as and when they happen. Expert and multidisciplinary decisions may be needed involving patients and those important to them in many instances.

The risk of major haemorrhage attributable to anticoagulation therapy is typically between 0.5% and 1.0% per year. When the risks of ischaemic stroke exceed this then anticoagulation is recommended. The optimal intensity of anticoagulation appears to be an INR of 2.0 to 3.0. However we are now seeing new drugs that are likely to replace warfarin. The holy grail of AF anticoagulation management is to find a drug more effective, but less harmful than warfarin that is cheap too.

HAS-BLED score for bleeding risk on oral anticoagulation in atrial fibrillation

| Feature | Score |

|---|---|

| Hypertension (SBP > 160 mmHg) | +1 |

| Abnormal renal (Dialysis, Creat > 200umol/l) /liver function (> 2x bilirubin or x3 ALT/AST/ALP) | +1/+1 |

| Stroke | +1 |

| Bleeding (any bleeding hx or anaemia) | +1 |

| Labile INRs (time in therapeutic range <60%) | +1 |

| Elderly Age > 65 | +1 |

| Drugs (anti-platelets, NSAIDs) or Alcohol | +1/+1 |

A HAS BLED score of 3 or more indicates increased one year bleed risk on anticoagulation (of 3.7 Bleeds per 100 patient years) sufficient to justify caution or more regular review. Increased risk of intracranial bleed, bleed requiring hospitalisation or a haemoglobin drop > 2g/L or that needs transfusion [Pisters R et al. 2010]

Warfarin anticoagulation titrated to an INR of 2.0-3.0 is recommended for the average patient with a CHA2DS2-VASc score =2 unless contraindicated (e.g., history of frequent falls, clinically significant bleeding, inability to obtain regular INR). Either Warfarin or Aspirin can be used for the average patient with a CHA2DS2-VASc score of 1 depending on physician discretion and patient preference. Aspirin 75-325 mg daily or no treatment may be reasonable depending on patient preference for the average patient with a CHA2DS2-VASc score of 0.

investigations

Those with AF should have an ECG, CXR, FBC, WCC and TFT as well as a cardiac echo. Various Cardiac structural defects can lead to the formation of intracardiac thrombi and cardioembolism. If suspected the first investigations include a clinical history and a search for any determinants that will give a clue. Cardiac symptoms suggestive of ischaemic heart disease, chest pain, breathlessness and palpitations which could suggest an ischaemic cardiomyopathy. A history of rheumatic fever could suggest valvular disease. A history of excess alcohol might suggest an alcoholic cardiomyopathy. Cardiomyopathy may also be seen with HIV. Examination may reveal heart failure, rashes, AF, signs of chronic liver disease, nicotine staining, hypertension and murmurs. An ECG,CXR and then Echo will be useful. A troponin may be useful acutely if recent myocardial infarction is suspected. Temperature and stigmata for endocarditis must always be considered.

Management

Acute care is not really for discussion here and can be found in the links below other than to say that those who are haemodynamically unstable should be considered for emergency DC cardioversion. In stable patients with recent-onset AF/ atrial flutter (AFL), a strategy of rate control or rhythm control could be selected. Those with AF or AFL of ≥ 48 hours or uncertain duration should be considered for anticoagulation. In the acute ischaemic stroke setting anticoagulation is generally delayed until 7-14 days post ischaemic stroke and an Anti-platelet is given in the meantime. In a TIA anticoagulation can usually be commenced in clinic the same or next day.

Management of AF which is beyond the scope of this book. Management strategies of rhythm or rate control do not appear to significantly affect stroke risk. Cardioversion is associated with increased stroke risk so patients should be anticoagulated for at least 3-4 weeks prior unless the arrhythmia has only been present for less than 24 hours or TOE reliably shows no Left atrial appendage clot. All patients should be anticoagulated post cardioversion. Post op AF is seen in those post cardiac surgery and has a three fold risk of TIA/Stroke.

For patients with non-valvular AF with prior stroke, transient ischaemic attack (TIA), or a CHA2DS2-VASc score of 2 or greater, oral anticoagulants are recommended. The use of direct oral anticoagulants has revolutionised the cardioembolic management of non valvular AF. They have for many replaced warfarin. There are now at least 4 new oral anticoagulants available. These are listed below. Those with valvular AF need anticoagulated with warfarin. Many of these newer drugs are renally excreted so creatinine clearance should be checked before usage. Renal function should be evaluated before initiation of direct thrombin or factor Xa inhibitors and should be re-evaluated when clinically indicated and at least annually. For patients with atrial flutter, antithrombotic therapy is recommended using the same risk profile as for AF. If the creatinine clearance < 15 ml/min then switch to Warfarin.

Anticoagulants

| Drug | Mechanism | Dosing advice | Antidote if active bleeding |

|---|---|---|---|

| Warfarin x mg OD | Vitamin K antagonist | Give sufficient to get INR 2-3 or 2.5-3.5 for high risk patients. Many interactions and dietary advice which require close monitoring | Vitamin K and Octaplex/Beriplex |

| Dabigatran 150 mg BD | Thrombin inhibitor | Avoid if avoid if creatinine clearance < 30 mL/minute. Reduce dose to 110 mg BD in those over 80 or if creatinine clearance 30-50 mL/minute or on Verapamil | Praxbind |

| Apixaban 5 mg BD | Factor Xa Inhibitor | reduce dose to 2.5 mg BD if creatinine clearance 15-29 mL/minute, or if serum-creatinine ≥ 133 micromol/litre and age ≥ 80 years or body-weight ≤ 60kg. Avoid if creatinine clearance less than 15 mL/minute | Octaplex/Beriplex |

| Rivaroxaban 20 mg OD | Factor Xa Inhibitor | If creatinine clearance 15-49 mL/minute reduce dose to 15 mg OD. Avoid if creatinine clearance < 15 mL/minute | Octaplex/Beriplex |

| Edoxaban 60 mg OD | Factor Xa Inhibitor | Reduce dose to 30 mg OD in moderate to severe renal impairment; avoid in end stage renal disease or in dialysis. Reduce dose to 30 mg OD in patients weighing ≤ 60 kg | Octaplex/Beriplex |

Left atrial appendage occlusion

Anticoagulation is the standard treatment of choice to reduce the risk and size of cardioembolic stroke. When anticoagulants are contraindicated due to excessive bleeding risk then Percutaneous Left atrial appendage oclusion may be considered. Patients selected should be those patients with AF with a high stroke risk and contraindications for Oral Anticoagulation. An excellent review can be found here. It is an evolving field and perhaps best if those undergoing the procedure do so as part of a RCT.

References and further reading

- Management of Atrial fibrillation 2016 ESC Clinical Practice Guidelines

- 2014 AHA/ACC/HRS Guideline for the Management of Patients With Atrial Fibrillation: Executive Summary

- Atrial fibrillation: management Clinical guideline [CG180] Published date: June 2014 Last updated: August 2014

- Canadian Cardiovascular guidelines on AF 2010

| Note: The plan is to keep the website free through donations and advertisers that do not present any conflicts of interest. I am keen to advertise courses and conferences. If you have found the site useful or have any constructive comments please write to me at drokane (at) gmail.com. I keep a list of patrons to whom I am indebted who have contributed. If you would like to advertise a course or conference then please contact me directly for costs and to discuss a sponsored link from this site. |